- Could Your Grocery Store Meat Be Causing Recurring UTIs?

- Are You Making This Expensive Thermostat Error This Winter?

- Recognizing the Signs of Hypothyroidism

- 10 Strategies to Overcome Insomnia

- Could Artificial Sweeteners Be Aging the Brain Faster?

- Techniques for Soothing Your Nervous System

- Does the Water in Your House Smell Funny? Here’s Why

- Can a Daily Dose of Apple Cider Vinegar Actually Aid Weight Loss?

- 6 Health Beverages That Can Actually Spike Your Blood Sugar

- Treatment Options for Social Anxiety Disorder

Music Therapy Helps Preemie Babies Thrive

The soothing sound of mom singing may help premature newborns breathe easier, a new review finds.

The analysis, of over a dozen clinical trials, found that music therapy helped stabilize premature newborns’ breathing rate during their time in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU).

For the most part, music therapy involved mothers singing to their babies (though some studies used recordings of mom’s voice). And that’s key, the researchers said.

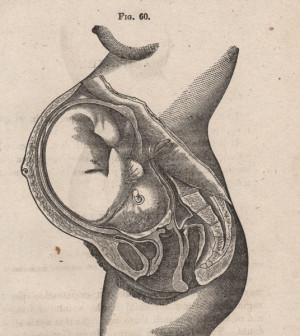

“Full-term infants can recognize the mother’s voice at birth,” explained researcher Lucja Bieleninik. “This connection is important to foster in premature infants, whose last months of gestation are instead spent outside of the womb.”

Plus, when mom or dad sing, they can change their voices — getting quieter, for example, when the baby seems to be falling asleep, explained Bieleninik, a postdoctoral researcher at the Grieg Academy Music Therapy Research Center, in Bergen, Norway.

In essence, music therapy begins in the womb, said Joanne Loewy. She’s director of the Mount Sinai Health System’s Louis Armstrong Center for Music and Medicine, in New York City.

“The first drummer you ever hear is your mother’s heart,” said Loewy, who wasn’t involved in the review. “You hear the ‘whoosh’ sounds of the womb.”

According to Loewy, “good music therapy” involves those same elements: a simple, predictable rhythm, periodic lulls and the familiar sound of mom’s voice.

In her own research, Loewy has found that live music in the NICU — sung or played — can help stabilize preemies’ heart rate and breathing, aid sleep and encourage “quiet alert” time. The live music involved either a parent singing a lullaby, a gato box that simulates the sound of a heartbeat, or an ocean disc that emulates the whooshing sounds of the womb.

What’s more, parents who sang to their infants said it lowered their stress levels.

That’s a pattern Bieleninik and her colleagues saw across the studies they reviewed: Mothers’ stress levels declined when they sang to their preemies in the NICU.

“By incorporating parents as active partners in music therapy, we can positively affect both preterm infants and their parents,” Bieleninik said.

For the study, the researchers pooled the results of 14 clinical trials involving close to 1,000 preemies. The trials differed in how music therapy was delivered, but most included moms singing in the NICU and all involved a music therapist.

Overall, the researchers found, music therapy showed a clear effect on infants’ breathing rates. Babies who received music therapy were also discharged three days sooner than other NICU preemies — though the difference was not statistically significant.

Loewy, whose own study was included in the review, said the findings are important because they come from controlled clinical trials of “true music therapy.”

That’s different from simply piping recorded music into the NICU. “This is not just any old music,” she noted.

Bieleninik agreed. “Since preterm infants are neurologically immature, inappropriate sensory stimulation can actually do them harm,” she said.

Formal music therapy is being offered in a growing number of NICUs in the United States and several other countries, Bieleninik said. She suggested that parents of newborn preemies ask to speak to a music therapist if one is available.

Part of the rationale behind the therapy, Loewy said, is that it’s “a tool parents can take home with them.”

There is, however, very little research into the long-term effects of music therapy. That’s a gap that needs to be filled, Bieleninik said.

Loewy had some advice for parents who want to use music to soothe their infants: Sing a simple lullaby at bedtime, holding your baby over your heart, skin to skin.

She said the “best” song is one that has meaning for parents — because it’s from their culture or because their parents sang it to them, for example.

And it doesn’t have to be a traditional lullaby.

“Parents can sing their favorite songs, modifying them into a lullaby style that is gentle, quiet, and ‘lulling,'” Bieleninik said.

“Often,” she added, “a very simple, nurturing use of the voice serves as the best medicine between preterm infant and parent at this vulnerable time.”

The study was published August 25 in the journal Pediatrics.

More information

Learn more about music therapy from the American Music Therapy Association.

Source: HealthDay

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.