- Could Your Grocery Store Meat Be Causing Recurring UTIs?

- Are You Making This Expensive Thermostat Error This Winter?

- Recognizing the Signs of Hypothyroidism

- 10 Strategies to Overcome Insomnia

- Could Artificial Sweeteners Be Aging the Brain Faster?

- Techniques for Soothing Your Nervous System

- Does the Water in Your House Smell Funny? Here’s Why

- Can a Daily Dose of Apple Cider Vinegar Actually Aid Weight Loss?

- 6 Health Beverages That Can Actually Spike Your Blood Sugar

- Treatment Options for Social Anxiety Disorder

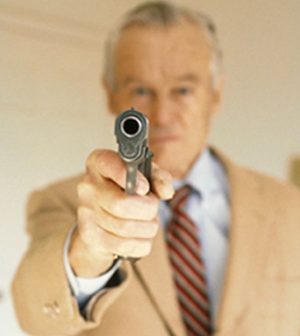

When Do You Take Guns From Someone With Dementia?

A diagnosis of dementia often triggers discussions about how to keep that person safe as the disease advances, but one serious safety concern that may be overlooked is gun ownership.

Somewhere between 40 percent and 60 percent of people with dementia have access to firearms in their homes, according to an editorial in the May 7 issue of the Annals of Internal Medicine. And guns are the most common way that people with dementia commit suicide.

Decisions about gun safety are similar to decisions that have to be made when people with dementia can no longer drive, the authors said.

“In my ideal world, people would lay out what they want to happen and who they want to take their guns when the time comes. People can set up a firearm trust,” said editorial lead author Dr. Emmy Betz, an associate professor of emergency medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

“But there often isn’t a clear point when you know it’s unsafe, and it’s a hard thing for people to tackle. People don’t want to upset the person with dementia, and providers don’t bring it up because they may be concerned about offending people,” she said.

In addition to the risk of suicide when there’s a firearm in the house, a gun also places loved ones and other caregivers at risk of being shot if a person with dementia is delusional or having hallucinations.

And that thought can be very difficult for family members to accept, Betz said.

Beth Kallmyer, vice president of care and support for the Alzheimer’s Association, agreed that the conversation about when to give up guns can be a hard one.

“You’re taking something away — a piece of their autonomy. Family members don’t want to do that. Autonomy should be respected whenever possible, but not when it bumps up against safety,” she said.

“Alzheimer’s isn’t just about memory loss. It’s also about loss of judgment and executive function and understanding contextual situations,” Kallmyer explained.

So what can families do to keep everyone — including the person with dementia — safe?

That likely depends on how advanced the dementia is. For people in the early stages of dementia, families can involve their loved one and perhaps come up with a firearms retirement date.

“When you can involve the person with Alzheimer’s in the process, it’s so much more empowering for them. You can say something like, ‘There may come a time when you can’t handle a firearm. I want you to tell me what you want to do with your guns then.’ People should always plan to do the safest thing they can do. It’s best to have firearms removed from the home, but every situation is different,” Kallmyer said.

If it’s early in the disease and someone is a hunter, a family member could say, “Let’s remove the guns now,” and agree to bring them back for supervised hunting trips, she said.

Once the disease has progressed to the moderate or severe stages, it’s probably not feasible to involve the person with dementia in the decision-making process any longer. At that point, guns should be removed from the home, locked up, stored separately from ammunition, loaded with fake bullets or have the trigger mechanism disabled, the editorial authors said.

Both Betz and Kallmyer said that disabling the trigger mechanism could put the person with dementia at risk if they ever have their gun out when they come in contact with the police. The law enforcement officials won’t have any way of knowing from a distance that the gun has been disabled.

“It’s not about the police or the government trying to confiscate your weapons, but how a family deals with this. It would be great to have guidance or a specific program from a group like the National Rifle Association,” Betz noted.

The editorial also offered screening recommendations for doctors to administer to patients. “The clinicians’ role is helping families get connected with the information they need,” Betz said.

Kallmyer noted that Medicare now offers a care-planning benefit under dementia care so that doctors can get reimbursed for the time they spend counseling families on what to expect as the disease progresses and what safety concerns they should address.

“It’s never too early to have a conversation about guns,” Kallmyer said. She added that if you need help on what to say to your loved one, the Alzheimer’s Association has a 24-hour hotline at (800) 272-3900.

More information

The Alzheimer’s Association has a number of downloadable brochures that address specific safety topics, including gun safety.

Source: HealthDay

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.