- Recognizing the Signs of Hypothyroidism

- 10 Strategies to Overcome Insomnia

- Could Artificial Sweeteners Be Aging the Brain Faster?

- Techniques for Soothing Your Nervous System

- Does the Water in Your House Smell Funny? Here’s Why

- Can a Daily Dose of Apple Cider Vinegar Actually Aid Weight Loss?

- 6 Health Beverages That Can Actually Spike Your Blood Sugar

- Treatment Options for Social Anxiety Disorder

- Understanding the Connection Between Anxiety and Depression

- How Daily Prunes Can Influence Cholesterol and Inflammation

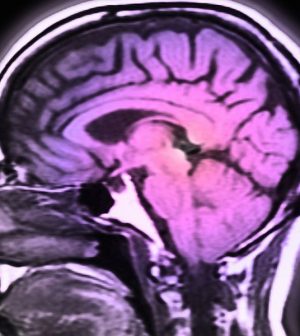

‘Rerouting’ Brain Blood Flow: Old Technique Could Be New Advance Against Strokes

Doctors are testing a decades-old surgical technique as a new way to treat certain stroke patients. And the preliminary results look promising, they say.

At issue are strokes caused by intracranial atherosclerosis, where blood vessels within the brain become hardened and narrowed.

Strokes occur when the blood supply to the brain is disrupted, depriving tissue of oxygen and nutrients. There can be various causes, and intracranial atherosclerosis is behind an estimated 10% to 15% of strokes in the United States, according to study author Dr. Nestor Gonzalez, a professor of neurosurgery at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles.

The outlook after those strokes, he said, is poorer compared to strokes with other causes, such as blockages in the neck’s carotid arteries.

Right now, patients are usually treated with medications — including blood thinners and high blood pressure drugs — to try to thwart a repeat stroke.

And while that does help, the recurrence rate is still high, Gonzalez said.

Surgical approaches have been tried — including placing stents in blocked brain arteries, similar to what’s commonly done for narrowed heart arteries.

But it just doesn’t work as well in the brain, said Dr. Louis Kim, chief of neurological surgery at Harborview Medical Center in Seattle.

Intracranial atherosclerosis is difficult to treat, Kim explained, because artery-clogging “plaques” may be scattered across the brain.

So Gonzalez and his colleagues have been studying a different approach — a surgical technique by the tongue-twister name of encephaloduroarteriosynangiosis (or EDAS, for short).

EDAS has been used for decades to treat a rare syndrome called Moyamoya disease, where blood vessels at the base of the skull progressively narrow and limit blood flow to the brain.

As neurosurgery goes, the approach is fairly simple and minimally invasive: a section of an artery in the scalp is re-routed to the surface of the brain. Over the next few weeks, new blood vessels begin to branch out from that artery into the brain, Gonzalez explained.

The idea is to supply better blood flow to areas of brain tissue at risk of stroke.

In a preliminary study of 28 patients treated with EDAS, Gonzalez and his team found that three — just under 11% — had another stroke in the next two years.

For comparison, they point to a clinical trial where patients with strokes caused by intracranial atherosclerosis were treated with standard medications. Their stroke recurrence rate was 37%.

While that is a substantial difference, there are big caveats, according to Kim, who was not involved in the study.

Comparisons between two different studies are not reliable evidence of effectiveness, he said. What’s needed is a clinical trial in which patients are randomly assigned to receive either standard care or standard care plus surgery.

Gonzalez agreed, and said that is exactly what is in the works: a larger trial at multiple U.S. medical centers funded by the National Institutes of Health. Patients will either receive the “best standard medical management,” or those same medications plus EDAS.

Kim said that while the current results are “pilot data,” the idea of testing EDAS for these stroke patients is a sound one.

“This is an exciting way to essentially recycle a well-known neurological procedure,” he said.

EDAS, Kim said, is a “simple” surgery, and since it has been around for a long time, doctors know a good deal about its safety.

“The operation is low-risk,” Kim said. A main issue, he noted, is that it does not always work well.

“In some cases, the new blood vessel growth is lackluster,” Kim said.

If adding EDAS to medication does prove to prevent more strokes, it would only be an option for a minority of stroke patients.

Gonzalez noted, though, that intracranial atherosclerosis seems to disproportionately affect Black, Hispanic and Asian Americans. It may cause closer to 20% of strokes in those groups.

The study was published in a recent issue of the journal Neurosurgery.

More information

The American Stroke Association has more on preventing repeat strokes.

SOURCES: Nestor Gonzalez, MD, professor, neurosurgery, and director, Neurovascular Laboratory, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles; Louis Kim, MD, MBA, chief, neurological surgery, Harborview Medical Center, Seattle, and professor, neurological surgery, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle; Neurosurgery, Jan. 19, 2021, online

Source: HealthDay

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.