- Recognizing the Signs of Hypothyroidism

- 10 Strategies to Overcome Insomnia

- Could Artificial Sweeteners Be Aging the Brain Faster?

- Techniques for Soothing Your Nervous System

- Does the Water in Your House Smell Funny? Here’s Why

- Can a Daily Dose of Apple Cider Vinegar Actually Aid Weight Loss?

- 6 Health Beverages That Can Actually Spike Your Blood Sugar

- Treatment Options for Social Anxiety Disorder

- Understanding the Connection Between Anxiety and Depression

- How Daily Prunes Can Influence Cholesterol and Inflammation

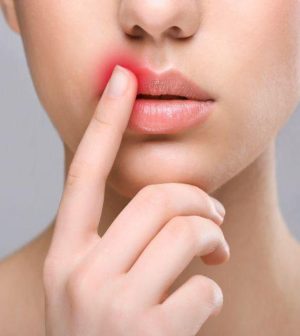

Animal Study Offers Hope for a Better Herpes Treatment

Aiming to deliver a one-two punch to the herpes virus, animal research on an experimental drug found it tackled active infections and reduced or eliminated the risk of future outbreaks.

Existing treatments, such as Zovirax, Valtrex or Famvir, are only effective at the first task; they can help treat cold sores and genital eruptions once a herpes outbreak occurs. But the new drug has a different goal in mind: a full cure from the threat of a chronic, lifelong disease.

How? By penetrating the nervous system to get at hidden virus that otherwise lies in wait, ready to trigger new outbreaks.

“Cold sores and genital herpes are caused by a virus called herpes simplex virus,” explained study author Gerald Kleymann. They’re the “blisters” you may notice on people’s lips and skin, he noted.

Kleymann is the CEO of the German company Innovative Molecules GmbH, which developed the drug.

Because herpes is so widespread, treating it is no small matter, he said. More than one of every two men and women are infected with herpes simplex virus type-1 (HSV-1), while roughly one-quarter are infected with genital herpes simplex virus type-2 (HSV-2), Kleymann noted.

“Lip blisters are considered a social stigma, and genital herpes can ruin your sex life,” Kleymann said. “[When] giving birth, the virus can be transmitted to the newborn, with fatal consequences. Also, the virus can be sight-impairing in case of an eye infection, or deadly in case of infected immunocompromised transplant patients, or in rare cases when patients develop a herpes encephalitis.”

On top of that, “once you are infected you carry the virus for life in your nerve cells,” he added. “And you may experience frequent recurrent disease lifelong.” The study team estimated that latent virus triggers recurring outbreaks in about 30% of patients.

Known as IM-250, the new drug has been tested on both mice and guinea pigs. In mice, the drug demonstrated an ability to promote a quicker recovery from acute outbreaks, while also safely killing latent virus lodged in infected cells. In guinea pigs, the drug appeared to reduce or completely eliminate the risk for recurring outbreaks. And the protective benefit endured well after completion of a week-long treatment session in the guinea pigs, the findings showed.

Beyond that, IM-250 also appeared to be effective even in treatment-resistant infections that failed to respond to standard herpes medications.

And that’s because “the new drug candidate tackles the virus where it hides and resides, namely in neurons of the face and genitals,” Kleymann said.

The findings were published June 16 in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

Dr. Amesh Adalja, a senior scholar with the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, in Baltimore, said the preliminary finding is “encouraging news.”

“Current treatments are effective at reducing the severity of infections, but are not able to eradicate the virus as it becomes latent in nerve cells, which the antivirals really can’t have much impact on. It is this latent reservoir of virus that causes recurrence,” Adalja said.

“Having a drug that is able to reduce the latent reservoir [of herpes virus] would be a major advantage in the treatment of herpes,” said Adalja, who was not involved in the German study.

Still, he cautioned that, as with all animal research, the finding “needs to be replicated in humans.”

On that front, Kleymann said that human clinical trials are already in the planning stages.

“If efficacy demonstrated in animal models translates into efficacy in humans, this will be a breakthrough,” Kleymann added, “since the drug candidate has the potential to affect the natural history of herpes simplex disease, and reduce the frequency of viral shedding and recurrent disease.”

More information

There’s more on herpes at the U.S. National Institutes of Health.

SOURCES: Gerald Kleymann, CEO, Innovative Molecules GmbH, Munich, Germany; Amesh Adalja, MD, senior scholar, Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, Baltimore; Science Translational Medicine, June 16, 2021

Source: HealthDay

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.