- 10 Strategies to Overcome Insomnia

- Could Artificial Sweeteners Be Aging the Brain Faster?

- Techniques for Soothing Your Nervous System

- Does the Water in Your House Smell Funny? Here’s Why

- Can a Daily Dose of Apple Cider Vinegar Actually Aid Weight Loss?

- 6 Health Beverages That Can Actually Spike Your Blood Sugar

- Treatment Options for Social Anxiety Disorder

- Understanding the Connection Between Anxiety and Depression

- How Daily Prunes Can Influence Cholesterol and Inflammation

- When to Take B12 for Better Absorption and Energy

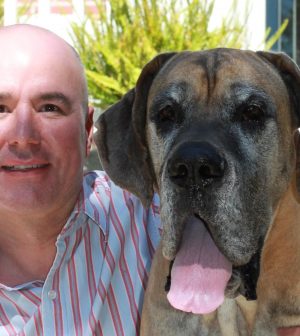

Unsung Heroes of the Pandemic: Dogs

Coping with the isolation, fear and sadness of the pandemic may have been a little easier if you had a trusting and loving dog by your side.

But you don’t need to tell that to Francois Martin, a researcher who studies the bonds between animals and humans. His two Great Danes helped him through the last two years, and he just completed a study that shows living with a dog gave folks a stronger sense of social support and eased some of the negative psychological effects of the pandemic.

“When you ask people, ‘Why is your dog important to you? What does your dog bring to you?’ People will say that it’s companionship. It’s the feeling of belonging to a group that includes your family dog. It keeps people busy,” said Martin, who is section leader for the Behavior and Welfare Group at Nestle Purina in St. Joseph, Mo. “If you have a dog, you have to walk the dog, you have to exercise the dog. It gives you a sense of purpose.

It’s “just plain fun,” Martin added. “I don’t know anybody who is as happy as my dogs to see me every day.”

His team saw the pandemic as a unique time to better understand how dogs provide social support to their owners.

To do that, they surveyed more than 1,500 participants who had dogs or wanted dogs that were not designated support animals. The survey, which was conducted on November 2020 and spring 2021, did not include owners of other types of pets because there is some evidence that different species may provide different types of support, Martin noted.

The researchers found that the depression scores were significantly lower for dog owners compared to the potential dog owners. The owners also had a significantly more positive attitude toward and commitment to pets.

The two groups did not have any difference in anxiety scores or happiness scores.

“In terms of trying to measure the effect of dog ownership on depression, for example, and anxiety, we saw that people that had low social support and that were affected a lot by COVID, you could see that the importance of their dog was stronger,” Martin said.

“If you’re already doing well and you’re not affected too much by the COVID situation, having a dog is not likely to help you be less depressed because you are already not very depressed, but we saw that people who were at the other end … you could measure the effect more precisely,” he noted.

In his particular situation, Martin already had a support system, so though he certainly enjoyed having his dogs around, that didn’t change his mood. Yet, it could for someone who might have been more personally impacted by the pandemic.

The study was published Dec. 15 in the journal PLOS One.

Pets can provide affection, companionship and entertainment, said Teri Wright, a mental health therapist in private practice in Santa Ana, Calif. However, it may not be the right choice for everyone.

“People ask me the question, ‘Do you think that animals, pets, dogs are good for depression, loneliness and psychiatric reasons?’ And I say it depends because they can also create a whole lot of stress. And so it depends on the person,” Wright said.

While Wright does have a dog at home, in her office she has a rabbit named Dusty who helps in her therapy practice. He serves as an ice breaker and helps people relax, she said.

Stanley Coren has written a lot about dogs and spent time during the pandemic with his two, a Nova Scotia duck tolling retriever named Ranger and a Cavalier King Charles spaniel named Ripley.

Coren, a professor emeritus in the Department of Psychology at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, was not affiliated with this study.

He said differences between anxiety and depression may be the reason why dogs had an impact on one but not the other for the participants in this study. It may be possible, Coren said, that a person petting their dog had a momentary reduction in stress or anxiety, rather than a long-term reduction.

“During COVID, there are just so many anxieties. The dog will relieve the social anxieties, but not the medical anxiety or the financial anxiety,” Coren suggested.

Dogs may help reduce depression because they provide a person with unconditional positive regard, Coren said. This can be especially helpful in times like the pandemic, particularly for someone without other social supports.

“If you live by yourself or you have minimal social supports, I think that a dog is a good adjunct to your mental health,” Coren said.

More work is needed to better understand the relationship between pet ownership, social support and how it affects owner well-being, according to the researchers.

“I think that if you are a dog lover and you’re in a position where you could acquire a dog and take care of him or her, I think it shows that you should, that dogs actually contribute to the overall well-being of people,” Martin said.

More information

The American Psychological Association has more on the human-animal bond.

SOURCES: Francois Martin, PhD, section leader, Behavior and Welfare Group, Nestle Purina, St. Joseph, Mo.; Teri Wright, PhD, mental health therapist, private practice, Santa Ana, Calif.; Stanley Coren, PhD, professor emeritus, Department of Psychology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver; PLOS One, Dec. 15, 2021

Source: HealthDay

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.