- Could Artificial Sweeteners Be Aging the Brain Faster?

- Techniques for Soothing Your Nervous System

- Does the Water in Your House Smell Funny? Here’s Why

- Can a Daily Dose of Apple Cider Vinegar Actually Aid Weight Loss?

- 6 Health Beverages That Can Actually Spike Your Blood Sugar

- Treatment Options for Social Anxiety Disorder

- Understanding the Connection Between Anxiety and Depression

- How Daily Prunes Can Influence Cholesterol and Inflammation

- When to Take B12 for Better Absorption and Energy

- Epsom Salts: Health Benefits and Uses

Scientists Design Skin Patch That Takes Ultrasound Images

(HealthDay News) – The future of ultrasound imaging could be a sticker affixed to the skin that can transmit images continuously for 48 hours.

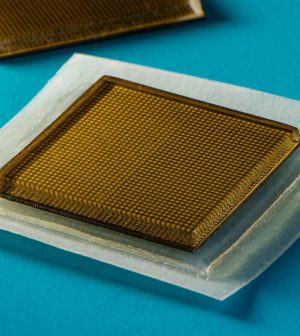

Researchers at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) have created a postage stamp-sized device that creates live, high-resolution images. They reported on their progress this week.

“We believe we’ve opened a new era of wearable imaging: With a few patches on your body, you could see your internal organs,” said co-senior study author Xuanhe Zhao, a professor of mechanical engineering and civil and environmental engineering at MIT.

The sticker — about 3/4-inch across and about 1/10-inch thick — could be a substitute for bulky, specialized ultrasound equipment available only in hospitals and doctor’s office, where technicians apply a gel to the skin and then use a wand or probe to direct sound waves into the body.

The waves reflect back high-resolution images of a major blood vessels and deeper organs such as the heart, lungs and stomach. While some hospitals already have probes affixed to robotic arms that can provide imaging for extended periods, the ultrasound gel dries over time.

For now, the stickers would still have to be connected to instruments, but Zhao and other researchers are working on a way to operate them wirelessly.

That opens up the possibility of patients wearing them at home or buying them at a drug store. Even in their current design, they could eliminate the need for a technician to hold a probe in place for a long time.

In the study, the patches adhered well to the skin, enabling researchers to capture images even if volunteers moved from sitting to standing, jogging and biking.

“We envision a few patches adhered to different locations on the body, and the patches would communicate with your cellphone, where AI algorithms would analyze the images on demand,” Zhao explained in an MIT news release.

A different approach tested — stretchable ultrasound probes — yielded images with poor resolution.

“[A] Wearable ultrasound imaging tool would have huge potential in the future of clinical diagnosis. However, the resolution and imaging duration of existing ultrasound patches is relatively low, and they cannot image deep organs,” said co-lead author Chonghe Wang, a graduate student who works in Zhao’s Lab.

The MIT team’s new ultrasound sticker produces higher resolution images by pairing a stretchy adhesive layer with a rigid array of transducers (they convert energy from one form to another). In the middle is a solid hydrogel that transmits sound waves. The adhesive layer is made from two thin layers of elastomer.

“The elastomer prevents dehydration of hydrogel,” co-lead author Xiaoyu Chen explained. “Only when hydrogel is highly hydrated can acoustic waves penetrate effectively and give high-resolution imaging of internal organs.”

Healthy volunteers wore the stickers on various areas, including the neck, chest, abdomen and arms. The stickers produced clear images of underlying structures, including the changing diameter of major blood vessels, for up to 48 hours. They stayed attached while volunteers sat, stood, jogged, biked and lifted weights.

They showed how the heart changes shape as it exerts during exercise and how the stomach swells, then shrinks, as volunteers drank and then eliminated juice. Researchers also could detect signs of temporary micro-damage in muscles as volunteers lifted weights.

“With imaging, we might be able to capture the moment in a workout before overuse, and stop before muscles become sore,” Chen said. “We do not know when that moment might be yet, but now we can provide imaging data that experts can interpret.”

In addition to working on wireless technology for the stickers, the team is developing software algorithms based on artificial intelligence that can better interpret the ultrasound images.

Zhao thinks patients may one day be able to buy stickers that could be used to monitor internal organs, the progression of tumors and development of fetuses in the womb.

“We imagine we could have a box of stickers, each designed to image a different location of the body,” Zhao said. “We believe this represents a breakthrough in wearable devices and medical imaging.”

The findings were published July 28 in Science.

More information

The National Institute of Biomedical imaging and Bioengineering has more on ultrasound.

SOURCE: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, news release, July 28, 2022

Source: HealthDay

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.