- Are You Making This Expensive Thermostat Error This Winter?

- Recognizing the Signs of Hypothyroidism

- 10 Strategies to Overcome Insomnia

- Could Artificial Sweeteners Be Aging the Brain Faster?

- Techniques for Soothing Your Nervous System

- Does the Water in Your House Smell Funny? Here’s Why

- Can a Daily Dose of Apple Cider Vinegar Actually Aid Weight Loss?

- 6 Health Beverages That Can Actually Spike Your Blood Sugar

- Treatment Options for Social Anxiety Disorder

- Understanding the Connection Between Anxiety and Depression

Vinegar May Be Cheap, Safe Way to Kill TB Germ

A potent weapon against a dangerous class of bacteria may be as close as the kitchen cupboard, new research suggests.

Scientists say common vinegar may be an inexpensive, non-toxic and effective way to kill increasingly drug-resistant mycobacteria — including the germ that causes tuberculosis.

Although researchers often use chlorine bleach to clean tuberculosis bacteria on surfaces, the study authors pointed out that bleach is also both toxic and corrosive. Meanwhile, other disinfectants may be too costly for tuberculosis labs in poor countries were the illness most often occurs.

But the research team found that acetic acid, the active ingredient in vinegar, does the trick cheaply and effectively.

“Mycobacteria are known to cause tuberculosis and leprosy, but non-TB mycobacteria are common in the environment, even in tap water, and are resistant to commonly used disinfectants,” study senior author Howard Takiff, of the Venezuelan Institute of Scientific Investigation in Caracas, said in a news release from the American Society for Microbiology.

“When they contaminate the sites of surgery or cosmetic procedures, they cause serious infections,” he added. “Innately resistant to most antibiotics, they require months of therapy and can leave deforming scars.”

According to Takiff, the danger is especially high in less affluent nations.

“Many cosmetic procedures are performed outside of hospital settings in developing countries, where effective disinfectants are not available,” he explained. “These bacteria are emerging pathogens. How do you get rid of them?”

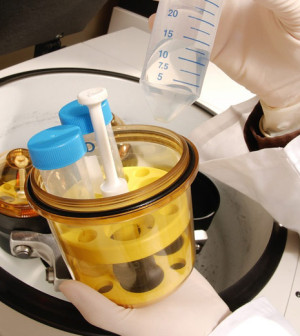

Takiff’s team accidentally discovered that vinegar could kill mycobacteria while testing a drug that needed to be dissolved in acetic acid. The test vial that contained only acetic acid — not the drug — still killed the bacteria, the team noticed.

Following this discovery, they tested various concentrations of acetic acid and different durations of exposure. With the help of scientists at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York City, the researchers found that strains of tuberculosis exposed to a 6 percent solution of acetic acid — slightly stronger than standard vinegar — effectively killed tuberculosis for 30 minutes after application.

The germ was reduced to undetectable levels, and that was true even for strains resistant to most antibiotics, Takiff’s team reported.

Meanwhile, in a laboratory in France, Takiff also tested how effective acetic acid was against one of the most drug-resistant strains of non-TB mycobacteria, M. abscessus. That research showed a stronger solution of 10 percent acetic acid for 30 minutes was needed to effectively kill the germ. This solution was still effective when they added albumin protein and red blood cells to mimic what might happen in real health care settings.

Safety didn’t seem to be an issue. The study, published online Feb. 25 in the journal mBio, found that even a 25 percent acetic acid solution is only a minor irritant and $100 could buy enough of this ingredient to disinfect up to about five gallons of tuberculosis cultures or clinical samples.

“There is a real need for less toxic and less expensive disinfectants that can eliminate TB and non-TB mycobacteria, especially in resource-poor countries,” said Takiff.

“For now this is simply an interesting observation,” he noted in the news release. “Vinegar has been used for thousands of years as a common disinfectant and we merely extended studies from the early 20th century on acetic acid. Whether it could be useful in the clinic or mycobacteriology labs for sterilizing medical equipment or disinfecting cultures or clinical specimens remains to be determined.”

More information

The U.S. National Library of Medicine has more on mycobacterial infections.

Source: HealthDay

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.