- Are You Making This Expensive Thermostat Error This Winter?

- Recognizing the Signs of Hypothyroidism

- 10 Strategies to Overcome Insomnia

- Could Artificial Sweeteners Be Aging the Brain Faster?

- Techniques for Soothing Your Nervous System

- Does the Water in Your House Smell Funny? Here’s Why

- Can a Daily Dose of Apple Cider Vinegar Actually Aid Weight Loss?

- 6 Health Beverages That Can Actually Spike Your Blood Sugar

- Treatment Options for Social Anxiety Disorder

- Understanding the Connection Between Anxiety and Depression

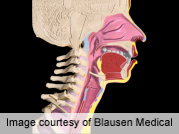

Treatment May Prevent Esophagus Condition From Progressing to Cancer

Using radio-frequency waves to treat certain cases of Barrett’s esophagus can substantially cut people’s risk of progressing to esophageal cancer, a new clinical trial suggests.

The trial, reported in the March 26 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association, was stopped early because the benefit of the treatment — called radio-frequency ablation — was so clear.

Still, the procedure is only for certain patients, and experts cautioned that there are some barriers to using it in the “real world.”

In the United States and Europe, about 2 percent to 6 percent of adults have Barrett’s, in which the lining the esophagus gradually morphs to resemble the lining of the intestines. The cause is unclear, but people with chronic heartburn are at increased risk.

Less than 1 percent of Barrett’s patients develop a rare cancer called esophageal adenocarcinoma. The risk is higher, however, in people who are found to have dysplasia — precancerous abnormalities in the esophageal lining.

But during the three-year study period, only one of 68 patients given radio-frequency ablation developed adenocarcinoma. That compared with six of 68 who were given standard care — “watchful waiting,” with periodic biopsies to see if the precancerous tissue was progressing.

Put another way, the treatment cut the risk of esophageal cancer from almost 9 percent to 1.5 percent over three years.

What’s most significant, the researchers said, is that the study patients all had low-grade dysplasia, which means the abnormalities are less severe and have a good chance of never progressing to cancer.

Until now, there has been agreement that ablation can be used for more-aggressive, “high-grade” abnormalities, said Dr. Arun Swaminath, a gastroenterologist at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City.

“But this study shows that you can treat low-grade dysplasia and actually reduce the risk of evolution to high-grade dysplasia or esophageal cancer,” said Swaminath, who was not involved in the research.

During ablation, a doctor uses radio waves to essentially burn away abnormal Barrett’s tissue, usually over a few separate treatments. That’s done with an electrode mounted on an endoscope that is threaded down the throat and into the esophagus — the roughly foot-long tube that carries food to the stomach.

Ablation carries risks, including bleeding and a narrowing in the esophagus that requires a procedure to widen it again. And since most low-grade abnormalities never progress to cancer, the idea of treating them with ablation has been controversial.

And it will probably still be controversial, said Dr. Klaus Monkemuller, a gastroenterologist at the University of Alabama at Birmingham who wrote an editorial published with the study.

But Monkemuller said he thinks ablation is a good option. “To me, this therapy changes the paradigm of ‘watch and wait,'” he said.

Dr. Jacques Bergman, the study’s senior author, agreed. “I feel this study shows that Barrett’s patients with a reliable diagnosis of low-grade dysplasia are at such a significant risk of progression that they should be strongly considered as candidates for ablation,” said Bergman, of the Academic Medical Center Amsterdam, in the Netherlands.

The catch, though, is the “reliable diagnosis.” Spotting true low-grade dysplasia is partly art. A pathologist studies a tissue sample from the esophagus and makes a judgment call — and two pathologists can look at the same sample and see different things.

“This is the Achilles’ heel of implementing our study,” Bergman said. The patients in his study all had their initial diagnosis of low-grade abnormalities confirmed by an “expert” pathology panel pulled together for the research.

Even then, more than one-quarter of the patients who underwent watchful waiting saw their precancerous tissue just go away.

Monkemuller said one option for people with low-grade abnormalities could be to put off ablation therapy until a follow-up biopsy — perhaps six months later — shows the condition is still present.

And patients can always ask that their diagnosis be confirmed by a second doctor, he said.

Another real-world issue is paying for the procedure. Right now, patients with low-grade abnormalities can have difficulty getting insurance coverage for ablation, Monkemuller said. He added, however, that the evidence from this study might help change that.

More information

The U.S. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases has more on Barrett’s esophagus.

Source: HealthDay

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.