- Could Your Grocery Store Meat Be Causing Recurring UTIs?

- Are You Making This Expensive Thermostat Error This Winter?

- Recognizing the Signs of Hypothyroidism

- 10 Strategies to Overcome Insomnia

- Could Artificial Sweeteners Be Aging the Brain Faster?

- Techniques for Soothing Your Nervous System

- Does the Water in Your House Smell Funny? Here’s Why

- Can a Daily Dose of Apple Cider Vinegar Actually Aid Weight Loss?

- 6 Health Beverages That Can Actually Spike Your Blood Sugar

- Treatment Options for Social Anxiety Disorder

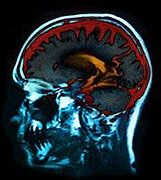

Brain Chemical May Help Control Tourette ‘Tics’

A particular brain chemical may help people with Tourette syndrome suppress the disorder’s characteristic “tics,” scientists report. They hope their discovery paves the way to new therapies for the developmental neurological disorder.

Tourette syndrome causes people to habitually make involuntary movements or sounds — commonly known as tics. Researchers think Tourette arises from an imbalance in “excitatory” and “inhibitory” activities in certain brain circuits; that results in jumbled, “noisy” messages being sent to movement-related areas of the brain.

The first signs of Tourette usually appear in childhood, but some people are eventually able to suppress their tics.

“We thought this might be because they could somehow ‘turn down the volume’ on the noisy motor signals” in the brain, explained Stephen Jackson, a professor at the University of Nottingham in the United Kingdom.

To delve into that question, Jackson’s team took brain scans of 15 teenagers with Tourette and a group of teens without the disorder. The investigators found that the Tourette group had higher levels of a brain chemical called GABA in one area of the brain — the supplementary motor area (SMA), which is involved in planning and performing movement.

The finding, reported online Thursday in Current Biology, is paradoxical on its surface. That’s because GABA inhibits brain cell activity, so it would seem logical for people with Tourette to show lower-than-normal levels of the chemical.

But Jackson explained what his team suspects: GABA levels increase in the SMA in response to Tourette tics.

The researchers found support for that when they asked the teens to tap their fingers while their brain activity was monitored. Among teens with Tourette, higher GABA concentrations corresponded to less activity in movement-related brain areas when they were preparing to move. In contrast, the teens without Tourette showed revved up activity in those brain regions.

“These results seem to suggest that the additional GABA is triggered by the Tourette,” Jackson said. The extra dose of GABA, in turn, may help quiet the excitability in the Tourette brain — “a bit like turning down the volume on a radio,” Jackson said.

Dr. Jeremiah Scharf, who directs the Tic Disorders Clinic at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, said, “This is a nice extension of recent research that’s putting together the pieces of what’s going wrong in the brains of people with Tourette.”

Scharf, who was not involved in the study, said it highlights an important point: Some brain differences seen in people with Tourette may help cause the symptoms, while others may actually help the brain “compensate.”

That idea fits with what’s known about the brain’s adaptability, Jackson noted. “The brain often undergoes changes in structure and function that can compensate for brain injury or a brain disorder, and thus reduce or even eradicate symptoms,” he said.

If elevated GABA is part of the brain’s response to Tourette tics, that finding points to possible new therapies, Jackson said. Noninvasive brain stimulation has been shown to boost GABA in targeted brain regions — though not in people with Tourette, specifically, Jackson noted.

He said his team hopes to test a technique called transcranial direct-current stimulation (TDCS) for speeding the brain’s natural — but slow — response to Tourette tics.

TDCS devices use electrodes to deliver low-level electrical pulses to specific areas of the brain. They are being studied for treating various types of brain disorders and injuries, such as Parkinson’s disease and damage from a stroke.

Scharf agreed that the results could eventually lead to new therapies, but much work remains. He said one question is, “Can you actually turn up just the GABA? Or would you affect excitatory activity, too?”

What is clear, according to Scharf, is that new therapies are needed. The available medications for Tourette include old antipsychotic drugs like haloperidol and pimozide, which block the brain chemical dopamine. They help only a minority of patients, Scharf said, and they can have “significant side effects,” including sedation.

A newer type of behavioral therapy, called cognitive behavioral intervention for tics, can be helpful — especially for children, Scharf said. Still, he added, “for a significant portion of patients, the current therapies either don’t help or don’t help enough.”

According to the U.S. National Institutes of Health, about 200,000 Americans have severe Tourette symptoms, while up to one in 100 have milder tics.

More information

The U.S. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke has more on Tourette syndrome.

Source: HealthDay

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.