- Could Your Grocery Store Meat Be Causing Recurring UTIs?

- Are You Making This Expensive Thermostat Error This Winter?

- Recognizing the Signs of Hypothyroidism

- 10 Strategies to Overcome Insomnia

- Could Artificial Sweeteners Be Aging the Brain Faster?

- Techniques for Soothing Your Nervous System

- Does the Water in Your House Smell Funny? Here’s Why

- Can a Daily Dose of Apple Cider Vinegar Actually Aid Weight Loss?

- 6 Health Beverages That Can Actually Spike Your Blood Sugar

- Treatment Options for Social Anxiety Disorder

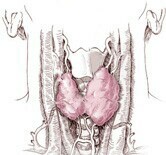

New Drug May Slow Recurrent Thyroid Cancer, Study Finds

A new thyroid cancer drug can delay the progression of the disease almost five times longer than a placebo in people with recurring cancer, according to results from a new clinical trial.

The oral drug, lenvatinib, is a targeted therapy that fights cancer by deterring the growth of new blood vessels that could help feed the cancer, researchers said.

Lenvatinib delayed progression of advanced thyroid cancer by 18 months, compared with four months for patients treated with a placebo, the trial found.

“It’s an encouraging time for the advancement of treating patients with many different kinds of cancer,” said Dr. Gregory Masters, of the new targeted therapies. Masters is an oncologist at Christiana Care Health System in Newark, Del., and a member of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

“We’re achieving a greater understanding of the pathways by which these cancers grow, and we’re using that understanding to block those pathways,” said Masters, who was not part of the study.

Results of the study, which was funded by drug manufacturer Eisai, were published in the Feb. 12 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine.

Historically, radioactive iodine has been the only treatment available to people with advanced thyroid cancer, said study leader Dr. Steven Sherman. He is associate vice provost for clinical research, and professor and chair of Endocrine Neoplasia and Hormonal Disorders at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

Unfortunately, more than half of patients do not respond to radioactive iodine treatment, Sherman said in a center news release. In addition, thyroid cancers tend to develop resistance to radioactive iodine over time, making the therapy less and less effective.

“It’s been a disease where it’s been very difficult to treat once it’s become resistant to radioactive iodine,” Masters said.

Lenvatinib must await U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval for use against thyroid cancer, Masters said. Another targeted drug, sorafenib, which works by encouraging the early death of cancer cells, was approved by the FDA in 2013 to treat thyroid cancer.

The international clinical trial for lenvatinib enrolled almost 400 patients from 21 countries, all of whom had thyroid cancer that had spread and become resistant to radioactive iodine.

Researchers treated 261 patients with lenvatinib, while 131 received a placebo. When their cancer started to progress again, patients in the placebo group could receive lenvatinib.

In addition to the nearly fivefold improvement in progression-free survival, the drug also appeared to be useful for treating more patients. About two-thirds of the patients given lenvatinib responded either fully or partially to the drug.

“In our study, we not only saw a dramatic improvement in progression-free survival, there was also a 65 percent response rate — almost unprecedented results for thyroid cancer patients with such advanced disease,” Sherman said.

The clinical trial did not observe any improvement in overall survival due to lenvatinib. However, Masters believes that the drug can’t help but improve patients’ overall survival, given its effectiveness in halting the cancer’s progression.

“Almost for sure, significant improvement like this in disease-free survival ultimately will translate into overall survival,” he said. “Sometimes you don’t see an improvement in overall survival because patients haven’t been followed long enough.”

Lenvatinib does come with some serious side effects, however. More than 40 percent of patients that received lenvatinib experienced some type of reaction while on the medication.

High blood pressure was the most common side effect, occurring in two out of three patients who had a reaction to the drug. Other side effects included diarrhea, fatigue, nausea, and decreased appetite and weight.

There were deaths related to side effects. Six of 20 deaths that occurred during the treatment period were determined to be drug-related. In addition, 37 patients discontinued the drug because of adverse effects, according to the study.

Sherman and Masters both said these side effects can be dealt with, either by adjusting dosage or by treating each of the side effects as individual symptoms. For example, blood pressure medication can be provided to those with high blood pressure due to lenvatinib.

But the impact of these side effects on a patient’s quality of life will need to be weighed, as well as the drug’s as-yet-unknown effect on overall survival, said Dr. Len Lichtenfeld, deputy chief medical officer for the American Cancer Society.

“These results are impressive as far as they go, meaning we don’t know yet whether it improves the survival outlook for these patients,” Lichtenfeld said. “We don’t know if it’s going to help people live longer, and given side effects we don’t know if it will help them live better.”

More information

For more information on targeted cancer therapies, visit the U.S. National Cancer Institute.

Source: HealthDay

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.