- Could Your Grocery Store Meat Be Causing Recurring UTIs?

- Are You Making This Expensive Thermostat Error This Winter?

- Recognizing the Signs of Hypothyroidism

- 10 Strategies to Overcome Insomnia

- Could Artificial Sweeteners Be Aging the Brain Faster?

- Techniques for Soothing Your Nervous System

- Does the Water in Your House Smell Funny? Here’s Why

- Can a Daily Dose of Apple Cider Vinegar Actually Aid Weight Loss?

- 6 Health Beverages That Can Actually Spike Your Blood Sugar

- Treatment Options for Social Anxiety Disorder

Less Toxic Transplant Treatment Offers Hope for Sickle Cell Patients

A new bone marrow transplant technique for adults with sickle cell disease may “cure” many patients. And it avoids the toxic effects associated with long-term use of anti-rejection drugs, a new study suggests.

This experimental technique mixes stem cells from a sibling with the patient’s own cells. Of 30 patients treated this way, many stopped using anti-rejection drugs within a year, and avoided serious side effects of transplants — rejection and graft-versus-host disease, in which donor cells attack the recipient cells, the researchers said.

“We can successfully reverse sickle cell disease with a partial bone marrow transplant in very sick adult patients without the need for long-term medications,” said researcher Dr. John Tisdale, a senior investigator at the U.S. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

In the United States, more than 90,000 people have sickle cell disease, a painful genetic disorder found mainly among blacks. Worldwide, millions of people have the disease.

Many adults with sickle cell disease have organ damage. This makes them ineligible for traditional transplants, which destroy all their bone marrow cells and use unmatched donor cells, he said. “Doing it this way would allow them access to a potential cure,” Tisdale said.

“Adult patients, in whom symptoms are very severe, should consider whether a transplant could be right for them,” he said. “A simple blood test for their siblings could tell them whether this approach is an option.”

One expert was enthusiastic about the report, published July 2 in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

“The outcomes look every bit as good, if not better, than anything reported so far,” said Dr. John DiPersio, chief of the division of oncology at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

“The issue is whether this can be extended to unrelated donors and to mismatched donors,” said DiPersio, also the author of an accompanying journal editorial.

A lack of suitable donors is the chief problem, he said. “So it’s still not going to cure the bulk of the patients without suitable donors, but for those that have siblings, this is a very attractive alternative,” DiPersio added.

The current study used cells from siblings that were a match to the patient’s cells. A new study, however, is underway that will test whether half-match cells from a parent will work as well, Tisdale said.

“This way we would be able to reach nearly every patient with sickle cell disease,” he said.

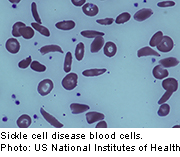

Sickle cell disease is a serious disorder in which the body makes crescent-shaped red blood cells.

Normal red blood cells are disc-shaped and move easily through the blood vessels. They contain an iron-rich protein called hemoglobin, which carries oxygen from the lungs to the rest of the body.

Sickle cells have abnormal hemoglobin and are stiff and sticky, blocking blood flow in the limbs and organs, causing relentless pain and organ damage. Infection risk is also increased.

Current treatment for sickle cell disease includes medication for pain and a drug (hydroxyurea) that helps normalize hemoglobin. Patients may also need blood transfusions as the disease worsens.

For the study, Tisdale’s team enrolled 30 patients, 16 to 65 years old, with severe sickle cell disease. Between 2004 and 2013, patients were given partial stem cell transplants with cells from a brother or sister.

Findings on the first 10 patients were reported in 2009, with nine of them successfully treated.

Of the remaining patients, 15 stopped taking anti-rejection medication one year after transplant and still had not had rejection or graft-versus-host disease during a median follow-up of roughly 3.4 years, the investigators found.

Overall, the partial transplant reversed the disease in 26 of 30 patients, the researchers said

The advantage of this procedure is that it gets people off drugs that weaken the immune system and cause side effects such as infection and joint swelling. Generally, transplants that don’t use matched donors require patients to take these drugs for the rest of their lives, the researchers noted.

More information

For more on sickle cell disease, visit the U.S. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Source: HealthDay

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.