- Comparing Whey and Plant-Based Protein: Which is Best?

- How Long Does Nicotine Remain in Your System?

- The Best Time of Day to Drink Bone Broth to Maximize Health Benefits

- 8 Ways to Increase Dopamine Naturally

- 7 Best Breads for Maintaining Stable Blood Sugar

- Gelatin vs. Collagen: Which is Best for Skin, Nails, and Joints?

- The Long-Term Effects of Daily Turmeric Supplements on Liver Health

- Could Your Grocery Store Meat Be Causing Recurring UTIs?

- Are You Making This Expensive Thermostat Error This Winter?

- Recognizing the Signs of Hypothyroidism

Blood Transfusions May Cut Risk of ‘Silent’ Stroke in Kids With Sickle Cell

Monthly blood transfusions may lower the chances of “silent” strokes in some children with sickle cell anemia, a new clinical trial indicates.

The study, reported in the Aug. 21 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine, found that in children with a previous silent stroke, monthly blood transfusions cut the rate of future strokes by more than half.

The researchers said their findings support screening children with sickle cell for evidence of silent stroke — something that is not routinely done now.

“Prior to this, there was no treatment, so the argument was, ‘Why screen?'” explained Dr. James Casella, vice chair of the clinical trial and director of pediatric hematology at Johns Hopkins Children’s Center in Baltimore. “Now we have a treatment to offer.”

However, Casella also stressed that “this study is a first step, not the last one.”

Many questions remain, he said. A big one is, do the blood transfusions have to be continued for life?

“It’s possible the treatment could be indefinite,” Casella said.

Sickle cell anemia is an inherited disease that mainly affects people of African, South or Central American or Mediterranean descent. In the United States, about one in 500 black children are born with the condition, according to the U.S. National Institutes of Health.

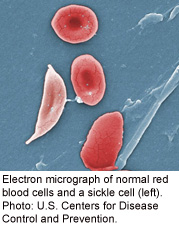

The central problem in sickle cell is that the body produces red blood cells that are crescent-shaped, rather than disc-shaped. Those abnormal cells tend to be sticky and can block blood flow.

About one-third of children develop problems with blood flow to the brain, including strokes and silent strokes — so called because they cause no obvious symptoms, but leave behind areas of tissue damage in the brain.

For the new study, Casella’s team used MRI brain scans to screen over 1,000 sickle cell patients between the ages of 5 and 15 for signs of a past silent stroke. In the end, 196 children with a previous stroke were randomly assigned to one of two groups: one received monthly blood transfusions, and one stayed with usual care.

Over three years, 6 percent of kids in the transfusion group had a new silent stroke or, in one case, a full-blown stroke. That compared with 14 percent of kids in the other group.

While the study found an association between blood transfusions and a lower risk of a silent stroke, it did not prove a direct cause-and-effect link.

What is the benefit of preventing silent strokes?

Casella said the brain injury can lower a child’s IQ and impair “executive function” — vital mental abilities such as focusing attention, planning and organizing.

In this study, there was no evidence that kids on transfusions had higher IQs or sharper mental function.

But the children were followed for only three years. And it’s reasonable to assume that preventing silent strokes would ultimately protect brain function, said Dr. Martin Steinberg, director of the Center of Excellence in Sickle Cell Disease at Boston University School of Medicine, who wrote an editorial published with the study.

The big questions, according to Steinberg, center on how to translate this treatment from a clinical trial, done at large academic medical centers, to the real world.

“The results of this trial are solid,” Steinberg said. “But it could be very difficult to do this in a community hospital setting, where the resources might not be there.”

Monthly transfusions are not a simple matter, Steinberg noted. For one, kids have to be monitored for side effects like “iron overload,” which is very common. Excess iron in the blood is potentially dangerous because the mineral can damage organs, and it may require treatment with special “chelating” drugs that draw excess iron from the blood.

And while this study ran for three years, blood transfusions would almost certainly have to continue for a longer time, according to Steinberg.

“I don’t think three years would be enough,” he said. “Sickle cell disease doesn’t go away.” He pointed to a 2005 study where transfusions were used to prevent overt — not silent — strokes; as soon as the treatment was stopped, patients’ stroke risk climbed again.

Casella said that based on his team’s findings, it’s reasonable for children with sickle cell to have an MRI brain scan before starting elementary school. If there are signs of a silent stroke, transfusions could be considered.

But whether that will become the standard remains to be seen. Casella agreed that the hospital resources might not be there, depending on where a family lives. And at least for now, insurers are unlikely to cover the costs.

Steinberg’s advice to parents: “First of all, if you can, go to a center with expertise in treating sickle cell disease. I wouldn’t run out and try to get MRI screening without that consultation.”

Casella said he is not suggesting blood transfusions are the final answer to sickle-cell-related strokes — and continuing research into alternatives is vital.

Steinberg agreed. “This is a difficult disease,” he said. “To make it better, the body has to make better red blood cells. Research is underway, and there are drugs under development. But they’re not here yet.”

More information

The U.S. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute has more on sickle cell anemia.

Source: HealthDay

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.