- 8 Ways to Increase Dopamine Naturally

- 7 Best Breads for Maintaining Stable Blood Sugar

- Gelatin vs. Collagen: Which is Best for Skin, Nails, and Joints?

- The Long-Term Effects of Daily Turmeric Supplements on Liver Health

- Could Your Grocery Store Meat Be Causing Recurring UTIs?

- Are You Making This Expensive Thermostat Error This Winter?

- Recognizing the Signs of Hypothyroidism

- 10 Strategies to Overcome Insomnia

- Could Artificial Sweeteners Be Aging the Brain Faster?

- Techniques for Soothing Your Nervous System

New Blood Pressure Guidelines Raise the Bar for Taking Medications

Fewer people should take medicine to control their high blood pressure, a new set of guidelines recommends.

Adults aged 60 or older should only take blood pressure medication if their blood pressure exceeds 150/90, which sets a higher bar for treatment than the current guideline of 140/90, according to the report, published online Dec. 18 in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

The expert panel that crafted the guidelines also recommends that diabetes and kidney patients younger than 60 be treated at the same point as everyone else that age, when their blood pressure exceeds 140/90. Until now, people with those chronic conditions have been prescribed medication when their blood pressure reading topped 130/80.

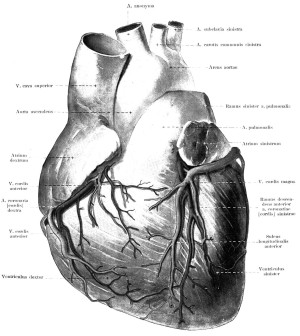

Blood pressure is the force exerted on the inner walls of blood vessels as the heart pumps blood to all parts of the body. The upper reading, known as the systolic pressure, measures that force as the heart contracts and pushes blood out of its chambers. The lower reading, known as diastolic pressure, measures that force as the heart relaxes between contractions. Adult blood pressure is considered normal at 120/80.

The recommendations are based on clinical evidence showing that stricter guidelines provided no additional benefit to patients, explained guidelines author Dr. Paul James, head of the department of family medicine at the University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine.

“We really couldn’t see additional health benefits by driving blood pressure lower than 150 in people over 60 [years of age],” James explained. “It was very clear that 150 was the best number.”

The American Heart Association (AHA) and the American College of Cardiology (ACC) did not review the new guidelines, but the AHA has expressed reservations about the panel’s conclusions.

“We are concerned that relaxing the recommendations may expose more persons to the problem of inadequately controlled blood pressure,” said AHA president-elect Dr. Elliott Antman, a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and a professor at Harvard Medical School in Boston.

In November, the AHA and ACC released their own joint set of treatment guidelines for high blood pressure, as well as new guidelines for the treatment of high cholesterol that could greatly expand the number of people taking cholesterol-lowering statins.

About one in three adults in the United States has high blood pressure, according to the U.S. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

The institute formed the Eighth Joint National Committee, or JNC 8, in 2008 to update the last set of high blood pressure treatment guidelines, which were issued in 2003.

In June 2013, the institute announced that it would no longer participate in the development of any clinical guidelines, including the blood pressure guidelines nearing completion.

However, the announcement came after the institute had reviewed the preliminary JNC 8 findings. The JNC 8 decided to forge ahead and finish the guidelines.

The recommendation to start seniors on medication at a higher blood pressure reading is based both on evidence of the medical benefit as well as concern over potential drug interactions and high drug costs, James said.

“The elderly are more likely to have other diseases that require medication. It’s not uncommon for me to see people who are on 10 different medications for various illnesses,” he said. “If we don’t see evidence of improved health benefits, then the question becomes why add those additional medicines?”

The definition of high blood pressure — anything above 140/90 — remains the same under the new guidelines, James said. Lifestyle changes should be used to treat people who have high blood pressure readings that fall below the level where medicine is needed, he explained.

The panel also recommended a “toolbox” of four different blood pressure medications that doctors could use treat patients — diuretics, calcium channel blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs).

“It gives options for physicians to begin treatment, and all classes have generic versions available,” James said. “This is a slight difference from JNC 7, where they preferred the diuretic class as the preferred first choice. We didn’t see significant differences between the four classes at improving health outcomes.”

James emphasized that these are treatment guidelines for doctors. “Patients should not read these guidelines and take themselves off medications,” he said. “These are recommendations that are intended for physicians who are highly trained professionals and will adapt them to individual patients’ needs.”

The JNC 8 reached its conclusions after reviewing more than 30 years of clinical studies. However, the AHA is concerned that those studies could not have assessed the full damage of long-term high blood pressure.

“The adverse effects of high blood pressure on a person’s health may take many, many years to develop, longer than the follow-up period of many of the trials included in the evidence review,” Antman said.

Epidemiologic evidence has shown that a lower blood pressure is associated with lower rates of strokes, heart failure and death, he added.

The guidelines issued by the AHA and the ACC call for lifestyle changes to treat people with a systolic pressure of 140 to 159 and a diastolic pressure of 90 to 99. Blood pressure levels greater than those should be treated by a combination of medication and lifestyle changes. Treatment would continue as long as the person had blood pressure higher than 140/90.

Even though the JNC 8 guidelines were not reviewed by the AHA or the ACC, the expert panel has provided enough transparency that its recommendations should be taken seriously, said Dr. Harold Sox, of the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice.

“They laid the evidence out in a really crystal clear way, and were really careful to make recommendations you could trace back to the evidence without asking, ‘How did they come up with that?'” Sox said.

“Even though they didn’t send the guidelines to AHA and ACC, their documentation of the review process was so thorough that I, for one, was convinced they couldn’t have learned anything more than what was learned in the initial review process,” Sox added.

Dr. Curtis Rimmerman, a staff cardiologist at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio, said he will weigh the new recommendations in his future treatment decisions.

“I’m going to have to go along with what I think are responsible people doing responsible acts,” he said. “I don’t think it’s going to change my practice very much, but I want to digest this information further. In some patients, I may relax some of my blood pressure goals, particularly among more elderly patients who are taking many medications.”

More information

For more information on blood pressure, visit the U.S. National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute.

Source: HealthDay

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.