- Comparing Whey and Plant-Based Protein: Which is Best?

- How Long Does Nicotine Remain in Your System?

- The Best Time of Day to Drink Bone Broth to Maximize Health Benefits

- 8 Ways to Increase Dopamine Naturally

- 7 Best Breads for Maintaining Stable Blood Sugar

- Gelatin vs. Collagen: Which is Best for Skin, Nails, and Joints?

- The Long-Term Effects of Daily Turmeric Supplements on Liver Health

- Could Your Grocery Store Meat Be Causing Recurring UTIs?

- Are You Making This Expensive Thermostat Error This Winter?

- Recognizing the Signs of Hypothyroidism

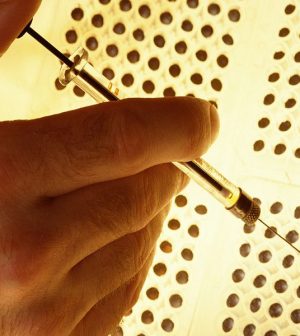

Experimental Gene-Targeted Drug Hits Cancer Where It Lives

An experimental drug that targets a specific gene mutation can battle a range of advanced cancers in adults and children, researchers are reporting.

The genetic abnormality is known as a TRK fusion, and it’s found in only a small percentage of all cancers. So the drug, called larotrectinib, is no panacea.

But researchers found that among 50 patients with TRK fusions, 76 percent saw their cancer regress after starting larotrectinib — regardless of their age or type of cancer.

For most of those patients — 79 percent — the response has lasted at least one year, according to lead researcher Dr. David Hyman.

“There are few therapies that have had that kind of success for patients like these,” said Hyman, an oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City.

Dr. William Oh, an oncologist who was not involved in the study, agreed.

“A 76 percent response rate for a new drug is extremely exciting,” said Oh, chief of hematology and medical oncology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City.

“More importantly,” he added, “the responses have been durable, lasting over a year — which for some of these aggressive cancers is very promising.”

This is the latest drug to target flaws in genes that occur anywhere in the body instead of just going after an organ-specific tumor. The first drug to work this way — Keytruda (pembrolizumab) — was approved for targeted use by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration on May 24. (Keytruda had previously received traditional FDA-approval for some organ-specific cancers.)

Targeted therapies are designed to zero in on specific abnormalities found on tumor cells — with the aim of killing off the cancer while sparing healthy cells.

The patients in Hyman’s study had a range of cancers, including colon, lung, pancreatic and gastrointestinal tumors — as well as melanoma skin cancer and sarcoma, which arise in the bones or soft tissue like muscle or body fat.

But they also had some things in common: Their cancer had spread beyond its original tissue, sometimes to distant sites in the body. And they all had tumors marked by TRK fusions.

The abnormality is a “rare event,” Hyman said.

TRK fusions occur in only about 0.5 percent to 1 percent of common cancers, such as colon, breast and lung cancers. But Hyman said they are very common in certain rare cancers such as salivary gland cancer, a form of breast cancer that affects children, and a type of sarcoma in babies.

The abnormality arises when a TRK gene in a cancer cell joins with one of many potential “partner” genes. (Scientists have found more than 50 so far). That, Hyman explained, results in TRK fusion proteins that are constantly “turned on,” signaling the cancer cells to keep growing and dividing.

Larotrectinib, an oral medication, is designed to block that TRK activity wherever it occurs.

The new study involved 55 patients, including 12 children. So far, 50 have been on the drug long enough to track their progress.

Overall, Hyman said, about three-quarters have responded to treatment — meaning their cancer regressed by at least 30 percent. Of those patients, eight in 10 were still on the drug and responding at the one-year mark.

At this point, Hyman said, the longest treatment response has been 25 months and counting.

The most common side effects are fatigue and dizziness. “Patients do very well on it,” Hyman said. “You can have a good quality of life while you’re taking it.”

Last year, the FDA granted larotrectinib “breakthrough therapy” status. That helps speed the development and review process of promising new treatments for serious diseases.

Hyman said he couldn’t estimate how long an FDA approval could take.

If the drug is approved, then the question will be: Who should get tested for TRK fusions?

According to Hyman, patients with advanced-stage cancer would have the “greatest need.” And even though TRK fusions are uncommon, he thinks testing would be appropriate regardless of the cancer type.

Oh agreed. “TRK fusions are very rare, but in those patients who have them, the consequences with this drug appear to be very significant.”

Plus, Oh said, cancer patients are already being tested for other molecular abnormalities to see if they can benefit from targeted drugs. That testing is becoming technically easier and cheaper, he noted.

Dr. Sumanta Kumar Pal is a medical oncologist at City of Hope in Duarte, Calif., and chair of ASCO’s Cancer Communications Committee.

He said larotrectinib has the chance to be a “bit of game-changer. There are two important points: This drug may be active irrespective of the cancer site, and irrespective of age.”

And while the safety results were encouraging, “it’s difficult to draw conclusions based on such a small group of patients,” he added.

If the drug is approved by the FDA, Pal said it would make sense to “test early” for TRK fusions in patients with the rare cancers. But with many common cancers, “we’d probably stick with standard care, and then (test) only if that fails,” he said.

The study was funded by Loxo Oncology, Inc., which is developing larotrectinib. Hyman and some of his colleagues have received funding from or served as consultants to the company.

Hyman was scheduled to present the findings Saturday at the American Society of Clinical Oncology’s annual meeting, in Chicago. Study results presented at meetings are usually considered preliminary until they’re published in a peer-reviewed medical journal.

More information

The American Cancer Society has an overview of targeted cancer therapies.

Source: HealthDay

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.