- The Best Time of Day to Drink Bone Broth to Maximize Health Benefits

- 8 Ways to Increase Dopamine Naturally

- 7 Best Breads for Maintaining Stable Blood Sugar

- Gelatin vs. Collagen: Which is Best for Skin, Nails, and Joints?

- The Long-Term Effects of Daily Turmeric Supplements on Liver Health

- Could Your Grocery Store Meat Be Causing Recurring UTIs?

- Are You Making This Expensive Thermostat Error This Winter?

- Recognizing the Signs of Hypothyroidism

- 10 Strategies to Overcome Insomnia

- Could Artificial Sweeteners Be Aging the Brain Faster?

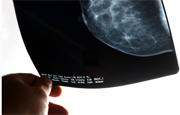

‘Freezing’ Technique May Work for Some Women With Early Breast Cancer

A tumor-freezing technique might offer a reasonable alternative to surgery for some women with early stage breast cancer, a preliminary study suggests.

The research, to be reported Wednesday at the American Society of Breast Surgeons annual meeting in Las Vegas, looked at a treatment called cryoablation. The approach, also called cryotherapy, uses substances such as liquid nitrogen or argon gas to freeze and destroy cancer cells.

Cryoablation is already an option for benign breast tumors called fibroadenomas, and for certain cancers — including some cases of skin, prostate and liver cancers. But researchers are just beginning to look into its potential for breast cancer.

The new study included 86 women with early stage invasive ductal breast cancer — which means the cancer had begun to invade the fatty tissue around the milk ducts.

The standard treatment is to surgically remove the cancer, usually followed by radiation. And it’s very effective; the five-year survival rate for stage 1 breast cancer is 100 percent, according to the American Cancer Society.

Still, some researchers want to find less invasive treatments — especially since breast cancer screening often finds tiny tumors, explained study author Dr. Rache Simmons.

Cryoablation fits the “less invasive” bill: A surgeon inserts a thin probe through a small incision in the skin, and then — guided by ultrasound — targets and freezes the tumor.

There are potential advantages of cryoablation over conventional surgery, according to Simmons, who is chief of breast surgery at New York Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center in New York City.

For one, it can be done with local anesthesia, and it avoids the pain and hospital stay that comes with surgery. “Cryoablation lends itself very well to the outpatient setting,” Simmons said.

And afterward, she noted, there’s no surgical scar.

But cryoablation also has to work. To put it to a preliminary test, Simmons and her colleagues treated all of their study patients with the procedure, then looked at the immediate results.

Overall, the treatment was only moderately successful: It got rid of all evidence of the cancer in 69 percent of the women. The rest of the women still had some “residual” cancer.

However, Simmons said, the treatment was “100 percent effective” in a subset of women with the smallest tumors — about 1 centimeter or less. So it’s possible that for those women, cryoablation could be a new option.

An expert not involved in the study urged caution, however. “We already have a very good treatment” in conventional surgery, said Dr. Subhakar Mutyala, associate director of the Scott & White Cancer Institute in Temple, Texas.

He noted that even when women are not able to have major surgery, minimally invasive surgery — which uses small incisions — may be an option.

“I’m not sure that there would be many good candidates for [cryoablation],” Mutyala said.

He added that further refinement of the cryotherapy technology might help boost the success rate seen in this study. But that remains to be seen.

Simmons and her team agree that further studies with “modifications” to the cryoablation technique could be useful.

But, Simmons said, it’s unlikely that cryoablation will ever be directly tested against standard surgery in a large clinical trial.

For now, she said that women could take heart in knowing that researchers are “actively searching” for less invasive treatments for early breast cancer.

Research presented at meetings should be viewed as preliminary until published in a peer-reviewed medical journal.

More information

The U.S. National Cancer Institute has more on cryotherapy.

Source: HealthDay

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.