- Comparing Whey and Plant-Based Protein: Which is Best?

- How Long Does Nicotine Remain in Your System?

- The Best Time of Day to Drink Bone Broth to Maximize Health Benefits

- 8 Ways to Increase Dopamine Naturally

- 7 Best Breads for Maintaining Stable Blood Sugar

- Gelatin vs. Collagen: Which is Best for Skin, Nails, and Joints?

- The Long-Term Effects of Daily Turmeric Supplements on Liver Health

- Could Your Grocery Store Meat Be Causing Recurring UTIs?

- Are You Making This Expensive Thermostat Error This Winter?

- Recognizing the Signs of Hypothyroidism

Gene Test May Help Predict Return of Early Breast Tumor, Study Says

For women who have early breast tumors surgically removed, a new genetic test may help predict the odds of a recurrence, a new study says.

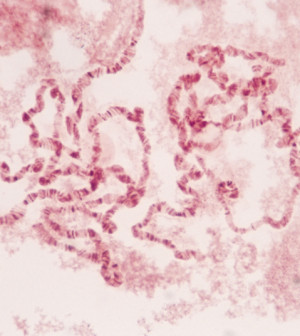

The research, presented Friday at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, focused on women with ductal carcinoma in situ.

This refers to abnormal cells in the lining of the milk ducts that may or may not progress to cancer that invades the surrounding breast tissue. Because there is no way of foretelling a progression, surgery is usually performed to remove the abnormality.

In the new study, researchers looked at whether a new test that zeroes in on certain genes can help predict which women will have their ductal carcinoma in situ recur after surgery. The goal is to aid doctors and patients in deciding on further treatment.

Right now, surgery is often followed by radiation and, in some cases, the drug tamoxifen, said Dr. Len Lichtenfeld, deputy chief medical officer for the American Cancer Society.

“But we’d all like to have a way to identify women who can avoid further treatment, and those who should have it,” said Lichtenfeld, who was not involved in the study.

He explained that doctors already consider a number of factors that affect a woman’s need for further treatment. Those include age, the size of the abnormality and its “grade” — a measure of how aggressive it appears.

“This gene test may add some information to the decision-making process,” Lichtenfeld said.

But he stressed that the ultimate value of the test — known as Oncotype DX — is not yet known, even though it is already on the market.

“At this juncture,” Lichtenfeld said, “the test looks interesting, but it’s not widely accepted as a way to guide treatment.”

Also, data and conclusions presented at meetings are usually considered preliminary until published in a peer-reviewed medical journal.

The Oncotype test analyzes certain cancer-linked genes to see how “active” they are, then gives the patient’s sample a score between 0 and 100.

The test had already been “validated” using tumor samples from patients enrolled in a clinical trial, explained Dr. Eileen Rakovitch, the lead researcher on the new study.

The study team wanted to see how the test performed for women treated in the real world, and not a clinical trial, said Rakovitch, a radiation oncologist at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Center in Toronto, Canada.

So she and her colleagues tested tumor samples from over 1,500 women treated for ductal carcinoma in situ from 1994 to 2003 — about 700 of whom received surgery only.

The researchers found that among those surgery-only patients, the higher the carcinoma score, the greater the risk of a recurrence over the next decade. For each 50-point increase in the score, the odds of a recurrence doubled.

But the test does not just lump women into lower- or higher-risk groups, Rakovitch noted.

“An individual woman gets information about her personal risk of recurrence over the next 10 years,” Rakovitch said.

And that is “much more informative,” she added, than relying on traditional factors, such as the tumor size and grade.

Still, the gene test is fairly new to the market, and Lichtenfeld said no one knows yet whether it’s making a difference in treatment decisions — or, most important, women’s long-term outlook.

In the United States, diagnoses of ductal carcinoma in situ have shot up because of routine mammography screening, Lichtenfeld noted. The abnormality rarely causes a lump, so it’s almost always caught because of mammography imaging.

According to the American Cancer Society, ductal carcinoma in situ accounts for about 20 percent of breast cancer diagnoses — and nearly all women with it are cured.

The hope, Rakovitch said, is that the Oncotype test will help some women avoid “overtreatment,” while others can feel more confident that they need additional treatment after surgery.

Lichtenfeld cautioned that if a doctor does recommend the gene test, women should make sure their insurance covers it. The test costs around $4,000, according to the nonprofit Breastcancer.org.

The study was partly funded by Genomic Health of Redwood City, Calif., which markets the Oncotype test.

More information

The U.S. National Cancer Institute has more on ductal carcinoma in situ.

Source: HealthDay

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.