- 7 Best Breads for Maintaining Stable Blood Sugar

- Gelatin vs. Collagen: Which is Best for Skin, Nails, and Joints?

- The Long-Term Effects of Daily Turmeric Supplements on Liver Health

- Could Your Grocery Store Meat Be Causing Recurring UTIs?

- Are You Making This Expensive Thermostat Error This Winter?

- Recognizing the Signs of Hypothyroidism

- 10 Strategies to Overcome Insomnia

- Could Artificial Sweeteners Be Aging the Brain Faster?

- Techniques for Soothing Your Nervous System

- Does the Water in Your House Smell Funny? Here’s Why

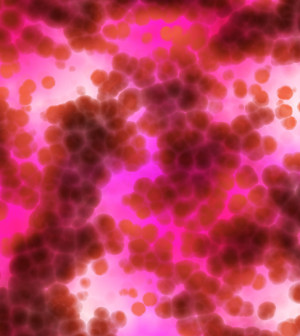

Immune Cell Therapy Shows Promise Against Deadly Blood Cancer

WEDNESDAY, Sept. 2, 2015An experimental therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) that uses a patient’s own immune cells may cure some patients and prolong survival in others with the blood cancer, researchers report.

The process of creating the therapy, called CTL019, begins with a patient’s own T cells, which are a type of white blood cell essential for an immune response. The cells are then reprogrammed to hunt and kill cancer cells. After chemotherapy the patient receives an infusion of the newly engineered cells, the researchers explained.

“This is a new, ultra-personalized and precision approach to treating cancer,” said lead researcher Dr. David Porter, director of blood and marrow transplantation at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

CLL is the most common type of adult leukemia, according to background information in the study. Survival is variable, ranging from two years to more than 20 years, the study authors said. Although effective treatment options are available, CLL is incurable with conventional therapies. Some patients can be cured with stem cell transplants, but not all patients are eligible, the researchers explained.

This study is a follow-up of 14 patients given the CTL019 treatment in 2010. All of the study volunteers had cancer that had relapsed or continued to progress after receiving conventional therapies, and few were eligible for bone marrow transplants, Porter said.

Eight of the 14 patients responded to the treatment. Four achieved a complete remission, including one patient who died 21 months after the therapy due to an infection that occurred after removal of skin cancer on his leg. The three other patients remained alive at the time of this analysis with no evidence of leukemia at 28, 52, and 53 months, the study found.

Four patients had a partial response to the therapy, with responses lasting an average of seven months. During follow-up, two of these patients died of disease progression — one at 10 and one at 27 months after receiving CTL019. Another study participant died after suffering a blood clot in the lung six months after treatment. The fourth patient had disease progression 13 months after therapy, but remained alive on other therapies at 36 months after the study treatment.

Unfortunately, the therapy didn’t work for everyone. Six patients didn’t respond to the therapy, and their cancer progressed within one to nine months. Study tests showed that the modified cells did not expand as robustly in these patients, the study authors said.

Side effects from the therapy included flu-like symptoms from proteins released into the bloodstream. For some patients these symptoms go away on their own, but Porter said that others needed medication.

Some patients developed lowered levels of antibodies needed to ward off infection. This was treated with infusions of antibodies to replace the patients’ missing ones, Porter said.

If the remissions seen in this study continue, and so far they have, it might be possible to treat patients even earlier in their disease, Porter suggested.

“As a one-time therapy, patients may not need repeated rounds of toxic chemotherapy, or prolonged treatment over many years to fight their cancer. It is still early in the development of this approach, but we are extremely optimistic about the potential,” Porter said.

“Cellular therapy is a ‘living drug’ — the fact that the cells can proliferate to such high levels magnifies or amplifies any potential response,” he said.

In addition, Porter pointed out, it was exciting to find that these cells persist in patients’ bodies for several years. This study provides evidence showing the cells not only survive in the body, but they remain functional, likely preventing relapse of the leukemia.

The report was published Sept. 2 in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

Susanna Greer, director of clinical research and immunology at the American Cancer Society, said, “This is an exciting observation. It’s one of those things we have our fingers crossed for that we will be able to apply this to a larger number of patients.”

Greer also thinks this approach might be used to treat other cancers.

Porter said his group and others have already shown a high remission rate in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. His team is also conducting a second, larger trial for CLL patients designed to define the optimal cell dose for patients. That trial is ongoing and still enrolling patients, he said.

“Clinical trials are underway testing a similar therapy for patients with pancreatic cancer, ovarian cancer, a specific type of lung cancer and even brain cancer,” he added.

Another expert, Dr. Jacqueline Barrientos of North Shore-LIJ Cancer Institute in Lake Success, N.Y., said, “The therapeutic landscape for patients with CLL is changing rapidly.” Barrientos is a medical oncologist and CLL research and treatment specialist.

“The breakthrough results of this study are proof of concept that immunotherapy may be a new way to treat our CLL patients in the future,” she said.

More information

For more on chronic lymphocytic leukemia, visit the American Cancer Society.

Source: HealthDay

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.