- Comparing Whey and Plant-Based Protein: Which is Best?

- How Long Does Nicotine Remain in Your System?

- The Best Time of Day to Drink Bone Broth to Maximize Health Benefits

- 8 Ways to Increase Dopamine Naturally

- 7 Best Breads for Maintaining Stable Blood Sugar

- Gelatin vs. Collagen: Which is Best for Skin, Nails, and Joints?

- The Long-Term Effects of Daily Turmeric Supplements on Liver Health

- Could Your Grocery Store Meat Be Causing Recurring UTIs?

- Are You Making This Expensive Thermostat Error This Winter?

- Recognizing the Signs of Hypothyroidism

Many Blood Cancer Patients Get Little Protection From COVID Vaccine

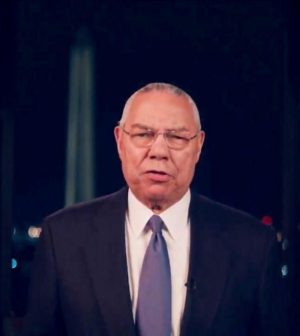

Anti-vaxxers felt their suspicions confirmed when former U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell died from COVID-19 complications in mid-October despite being fully vaccinated.

But Powell, 84, was being treated for blood cancer at the time of his death, and a new study reports that the COVID vaccines are producing little to no protection for some cancer patients.

Nearly 3 out of 5 blood cancer patients failed to mount an immune response against COVID after receiving a full two-dose course of the Pfizer vaccine, according to clinical trial results from the United Kingdom.

People with solid tumors also had a less robust response to COVID vaccination compared with healthy folks, researchers added.

The new study “demonstrates to us that people with both solid tumors and also blood cancers do not respond optimally to vaccines, and particularly to COVID vaccine,” said Dr. William Schaffner, medical director of the Bethesda, Md.-based National Foundation for Infectious Diseases. “They have demonstrated it with a sureness and a completeness that we didn’t have before.”

Powell died while battling multiple myeloma, a blood cancer that particularly impacts the immune system. He had been scheduled to receive a third COVID vaccine booster shot, but died before his appointment.

“Although we are well to try to get them to respond by giving them a third dose of vaccine, our expectations shouldn’t be too high, and neither should the patients’ [expectations],” Schaffner said.

For this trial, Dr. Sheeba Irshad, a senior clinical lecturer from King’s College London, and colleagues administered the Pfizer vaccine to 159 people, 128 of whom were cancer patients. They then tracked their immune response. The results were published Oct. 11 in the journal Cancer Cell.

The researchers found that only 36% of blood cancer patients achieved an immune response to COVID following full vaccination, compared with 78% of solid cancer patients and 88% of the healthy control participants.

The first dose of vaccine didn’t work particularly well in solid cancer patients, with only 38% developing an immune response to COVID. But a second dose given at either 3 or 12 weeks boosted protection.

Cancers tend to wreak havoc with the body’s immune system, particularly cancers of the blood, Schaffner said.

Blood cancers “frequently involve cells that interact with or are a part of the immune system — lymphomas, for example. The disease itself reduces the capacity of the immune system to function normally,” Schaffner said.

The study points out that older age — a known link to severe COVID — takes a back seat to cancer, said one expert.

“A cancer diagnosis seems to trump age as a risk factor for a weaker immune response,” said Dr. Julie Gralow, executive vice president and chief medical officer of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

The treatments used to cure cancer — chemotherapy, radiation therapy, immunotherapy — also can interfere with immune response, said Dr. Betty Hamilton, interim director of the Cleveland Clinic Blood and Marrow Transplant Program.

“We have had the sense that patients who are immunosuppressed or immunocompromised in some way have less response to the vaccine,” Hamilton said, citing cancer patients as well as patients undergoing organ transplant.

Still, cancer patients should get the COVID vaccine and booster, Hamilton and Schaffner said.

“We do still recommend vaccination for these patients because we do believe that a little bit of protection is better than none,” Hamilton said.

Best bet is to quarantine

But their best bet to stay COVID-safe is to quarantine, and for the people around them to get vaccinated and stick tight to public health recommendations, the experts said.

“If you are one of these people, or one of the people around these people, you have to be careful,” Schaffner said. “Use the masks. Be very careful with social distancing, and avoid crowds. And certainly the people around them should be vaccinated.”

Hamilton agreed.

“It’s really important to counsel these patients that they still need to be very careful in public and to wear masks and wash their hands frequently,” Hamilton said.

“My specialty is bone marrow transplant, and so our patients are extremely immunosuppressed,” she said. “Oftentimes after transplant they use these public health measures anyway. Even without COVID, they’ve been using these methods of avoiding crowded places and wearing masks and washing their hands frequently and avoiding people who are ill.”

This threat to cancer patients further emphasizes the need for as many people in the community as possible to get vaccinated against COVID, Hamilton and Schaffner added.

“If you permit this virus to circulate in the community, occasionally it will sneak through the perimeter that we create around these people. It can get in and infect one of these people and make them gravely ill,” Schaffner said.

“You can believe everyone around Colin Powell with an army’s precision was going to be protected. Nobody wanted to be the dreaded spreader who gave it to Colin Powell, but it got through to the Powell family anyway,” he continued. “That happens when the virus is still out there circulating in the community and hasn’t yet been suppressed optimally.”

And it’s not just people with cancer who would be protected by herd immunity to COVID, Schaffner said.

“There are many more frail people around us than we are used to, because medical science is such that people are living older. They’re living frailer. People with underlying serious illnesses like cancers of various kinds are living longer among us,” Schaffner said. “We all share a responsibility to help protect our frail brothers and sisters who live among us.”

More information

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has more on COVID-19 vaccines for immunocompromised patients.

SOURCES: William Schaffner, MD, medical director, National Foundation for Infectious Diseases, Bethesda, Md.; Julie Gralow, MD, executive vice president and chief medical officer, American Society of Clinical Oncology; Betty Hamilton, MD, interim director, Cleveland Clinic Blood and Marrow Transplant Program; Cancer Cell, Oct. 11, 2021

Source: HealthDay

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.