- Comparing Whey and Plant-Based Protein: Which is Best?

- How Long Does Nicotine Remain in Your System?

- The Best Time of Day to Drink Bone Broth to Maximize Health Benefits

- 8 Ways to Increase Dopamine Naturally

- 7 Best Breads for Maintaining Stable Blood Sugar

- Gelatin vs. Collagen: Which is Best for Skin, Nails, and Joints?

- The Long-Term Effects of Daily Turmeric Supplements on Liver Health

- Could Your Grocery Store Meat Be Causing Recurring UTIs?

- Are You Making This Expensive Thermostat Error This Winter?

- Recognizing the Signs of Hypothyroidism

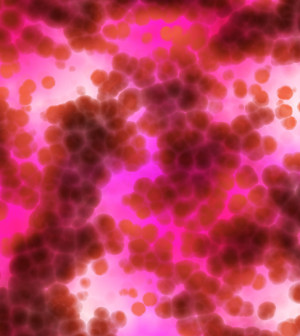

More Evidence Tamoxifen, Other Meds Help Limit Breast Cancer’s Spread

Treatment with tamoxifen or another class of drugs called aromatase inhibitors does cut breast cancer patients’ risk of developing cancer in their other breast, a new study finds.

Some breast cancers rely on estrogen to help them grow, and drugs like tamoxifen or the aromatase inhibitors (which include anastrozole) have long been prescribed to certain breast cancer survivors.

Tamoxifen blocks estrogen receptors in the breast cells to hamper cancer growth. Anastrozole stops estrogen production in fat tissue, which makes small amounts of the hormone.

According to background information in the new study, about 5 percent of breast cancer patients develop cancer in their other breast (contralateral breast cancer) within 10 years after their initial breast cancer diagnosis. Prior clinical trials had concluded that tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors reduce this risk, but their impact on actual patient treatment was unclear.

The new study was led by Gretchen Gierach, of the U.S. National Institutes of Health, and involved almost 7,500 women diagnosed with invasive breast cancer between 1990 and 2008.

Most of the patients were white and their average age at diagnosis was nearly 61. Tamoxifen was used by 52 percent of the patients for an average of just over three years.

Aromatase inhibitors were used by nearly 26 percent of the patients. About half of this group took aromatase inhibitors with tamoxifen for a median of 2.2 years, and about half took aromatase inhibitors alone for a median of almost three years.

During just over six years of follow-up, 248 of the patients in the study were diagnosed with a cancer appearing in the previously unaffected breast.

However, the risk of this happening declined the longer patients took tamoxifen, Gierach’s team found. Compared to those who did not take the drug, current users had a 66 percent lower risk after four years of taking tamoxifen. Risk reductions were smaller but still significant at least five years after stopping tamoxifen therapy, the study authors noted in a news release.

Use of aromatase inhibitors without tamoxifen was also associated with reduced risk of cancer in the previously unaffected breast, the findings showed.

Overall, for every 100 patients who’d survived at least five years, using tamoxifen for at least four years was estimated to prevent three cases of tumors spreading to the previously unaffected breast over a decade, the researchers said. That finding was specific to women with what are known as estrogen receptor-positive tumors, where the cancer is sensitive to the hormone.

Gierach’s team believes the findings support recommendations that breast cancer survivors “complete the full course” of whichever medication (tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitor) they’ve been prescribed.

Two oncologists each called the new findings “reassuring.”

One is Dr. Stephanie Bernik, who is chief of surgical oncology at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City. She believes that tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors are potentially life-saving, so the new findings are welcome.

“Many women have side effects from the drugs and although these side effects are often minor, they need encouragement to continue using the drug,” Bernik explained. “With more evidence showing that in real-life settings tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors help prevent recurrences, more women will continue to take the drug for longer periods of time.”

Dr. Nina D’Abreo directs the Breast Health Program at Winthrop-University Hospital in Mineola, N.Y. She believes the NIH trial confirms the benefits of the drugs as evidenced in prior studies, and may help dissuade some women from deciding to have the unaffected breast removed for preventive purposes.

D’Abreo said the study “also affirms that the duration of therapy matters, but even shorter use has benefits for the ‘real-world patient’ who cannot comply with the recommended five to 10 years.”

The findings were published online Oct. 6 in the journal JAMA Oncology.

More information

The U.S. National Cancer Institute has more on breast cancer.

Source: HealthDay

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.