- 7 Best Breads for Maintaining Stable Blood Sugar

- Gelatin vs. Collagen: Which is Best for Skin, Nails, and Joints?

- The Long-Term Effects of Daily Turmeric Supplements on Liver Health

- Could Your Grocery Store Meat Be Causing Recurring UTIs?

- Are You Making This Expensive Thermostat Error This Winter?

- Recognizing the Signs of Hypothyroidism

- 10 Strategies to Overcome Insomnia

- Could Artificial Sweeteners Be Aging the Brain Faster?

- Techniques for Soothing Your Nervous System

- Does the Water in Your House Smell Funny? Here’s Why

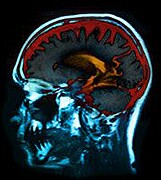

Technology May Help Surgeons Tell Brain Cancer From Healthy Tissue

Researchers are making progress in developing an ultrasound-like technology that helps brain surgeons distinguish between brain tumors and normal tissue.

In the new study, researchers report how the technology worked on human brain tissue. But, the technology hasn’t yet been tested in living people.

“Hopefully this summer we’ll unroll the first preliminary studies, and we’ll begin to use it in patients,” said study co-author Dr. Alfredo Quinones-Hinojosa, professor of neurological surgery and oncology and director of the Brain Tumor Surgery Program at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore. Currently, he said, “we agonize because many times we can’t tell what is tumor and what is normal brain.”

The study appears in the June 17 issue of Science Translational Medicine.

About 70,000 people are diagnosed with brain cancer in the United States each year, the American Brain Tumor Association says. Brain cancer kills about 14,000 Americans annually, the association reports.

Surgery is the recommended treatment in many cases. But it can be hard to tell where the tumor ends and healthy brain tissue begins.

“The more you take out of the cancer, the better for the patients,” said Quinones-Hinojosa.

However, removing the wrong kind of tissue can “potentially compromise things like speech or moving the arm or finger,” said study co-author Xingde Li, a professor of biomedical engineering at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. “You want to have a very precise guiding tool to tell you what to cut and not to cut.”

That’s where the new technology comes in. It relies on optical coherence tomography, which uses light to measure distance, somewhat like radar, the study authors explained.

“It works similarly to ultrasound, but has better resolution because light travels faster than sound,” said study lead author Carmen Kut, a Johns Hopkins University graduate student.

The technology produces color-coded maps that allow for better distinction between types of brain tissue, the researchers explained.

For the study, researchers tested the technology by analyzing human brain tissue — some of it cancerous — that had been removed from people. They analyzed the tissue in the laboratory and transplanted some into mice for more analysis.

If it works in people, “it will help by not only allowing us to see the tumor but also take more,” study co-author Quinones-Hinojosa said, “and extend the survival of patients.”

Other experts expressed some reservations. “Human brain tumors growing in the brains of animals do not fully reflect how they grow in human patients,” said Ruman Rahman, assistant professor in molecular neuro-oncology at the Children’s Brain Tumor Research Center at the University of Nottingham in England. “Therefore, it cannot be presumed that the technology will work just as well in patients as it has in the animals.”

Still, Rahman said, “This is potentially a breakthrough technology.”

Another brain tumor specialist, Peter Jarritt, deputy director of the NIHR Healthcare Technology Cooperative for Brain Injury in the United Kingdom, cautioned that the technology does not penetrate through a layer of blood, potentially limiting its use if there’s significant bleeding during an operation.

Study co-author Li expects the new technology to be cheaper in cost than some other forms of brain-scanning technology. In terms of side effects, he said the light doesn’t hurt the brain tissue.

In addition to brain cancers, Kut believes the new technology might prove useful in other cancers. It also might help surgeons avoid blood vessels during surgeries, she said.

More information

For more about brain tumors, see the U.S. National Cancer Institute.

Source: HealthDay

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.