- Comparing Whey and Plant-Based Protein: Which is Best?

- How Long Does Nicotine Remain in Your System?

- The Best Time of Day to Drink Bone Broth to Maximize Health Benefits

- 8 Ways to Increase Dopamine Naturally

- 7 Best Breads for Maintaining Stable Blood Sugar

- Gelatin vs. Collagen: Which is Best for Skin, Nails, and Joints?

- The Long-Term Effects of Daily Turmeric Supplements on Liver Health

- Could Your Grocery Store Meat Be Causing Recurring UTIs?

- Are You Making This Expensive Thermostat Error This Winter?

- Recognizing the Signs of Hypothyroidism

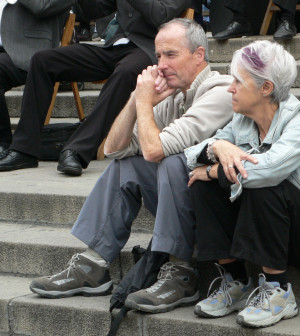

Many of Oldest Old Say They’re at Peace With Dying

People well into their 90s are often willing to talk about death, but they’re rarely asked about it, a new British study finds.

“Despite the dramatic rise in the number of people living into very old age, there is far too little discussion about what the ‘oldest old’ feel about the end of their lives,” said study leader Jane Fleming. “We know very little, too, about the difficult decisions concerning their end-of-life care.”

Fleming is with the University of Cambridge’s public health and primary care department.

The researchers interviewed several dozen people over 95 years old — or their relatives or caregivers if they were too frail — about their attitudes on death and end-of-life care.

According to the study, published April 5 in PLOS ONE, most had outlived their peers. Many felt they were living on “borrowed time.” They also felt grateful for each passing day, and didn’t worry too much about the future.

“It is only day-from-day when you get to 97,” said one participant.

The researchers noted that most of the older people interviewed felt prepared to die. “I’m ready to go,” said one woman. “I just say I’m the lady-in-waiting, waiting to go.”

In some cases, the participants felt as if they had become a burden on others or were anxious to finally reach the end of their long lives.

Many were more concerned about how they died than when. They hoped they would “slip away quietly” in their sleep and that their death would be painless. “I’d be quite happy if I went suddenly like that,” said one.

Few participants said they would want to be hospitalized if they became sick.

When asked if they would prefer lifesaving medical care or treatment to help them remain comfortable, most opted for comfort. Most were also not afraid of dying. For some, witnessing the peaceful death of others helped them manage their fears.

One woman recalled her parents’ deaths, saying, “They were alive, then they were dead, but it all went off as usual. Nothing really dramatic or anything. Why should it be any different for me?”

Funeral planning among the very old is more common than open discussions about death, the researchers found. Some had even made arrangements for themselves in advance.

“Death is clearly a part of life for people who have lived to such an old age, so the older people we interviewed were usually willing to discuss dying, a topic often avoided,” Fleming said in a university news release. To best support men and women dying at increasingly older ages, she said, “we need to understand their priorities as they near the end of life.”

Most participants had had end-of-life discussions with their doctor. But, rarely did these conversations take place among family members, said Fleming and her co-author Morag Farquhar, a senior research associate in the public health and primary care department at Cambridge.

“Having these conversations before it is too late can help ensure that an individual’s wishes, rather than going unspoken, can be heard,” Farquhar said in the news release.

More information

The U.S. National Institutes of Health provides more on preparing for the end of life.

Source: HealthDay

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.