- Comparing Whey and Plant-Based Protein: Which is Best?

- How Long Does Nicotine Remain in Your System?

- The Best Time of Day to Drink Bone Broth to Maximize Health Benefits

- 8 Ways to Increase Dopamine Naturally

- 7 Best Breads for Maintaining Stable Blood Sugar

- Gelatin vs. Collagen: Which is Best for Skin, Nails, and Joints?

- The Long-Term Effects of Daily Turmeric Supplements on Liver Health

- Could Your Grocery Store Meat Be Causing Recurring UTIs?

- Are You Making This Expensive Thermostat Error This Winter?

- Recognizing the Signs of Hypothyroidism

Implanted Defibrillators May Help Patients With Moderate Heart Failure

People with moderate heart failure may live longer with an implanted defibrillator, researchers report.

A normal heart’s pumping ability — called ejection fraction — is 50 percent to 70 percent. An ejection fraction below 50 percent signals the possible beginnings of heart failure, according to the American College of Cardiology.

Implanted defibrillators have shown a benefit in patients with advanced heart failure and ejection fractions of 30 percent or less. But whether patients with moderate heart failure might also benefit is the question this study tried to answer.

The answer was yes, the study authors said.

“Patients with an ejection fraction of 30 to 35 percent who receive an implantable defibrillator have better survival than similar patients with no implantable defibrillator,” said study author Dr. Sana Al-Khatib, an associate professor of medicine at Duke University in Durham, N.C.

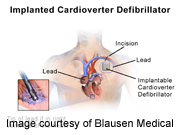

Implantable defibrillators are small devices put in the chest to monitor the heart’s rhythm and deliver small electrical shocks to help treat life-threatening heart rhythm disorders.

They have been proven to reduce sudden cardiac death or death from any cause in patients suffering from heart failure or in those who have had a heart attack and have ejection fractions of 35 percent or less, explained study co-author Dr. Gregg Fonarow, a professor of cardiology at the University of California, Los Angeles.

However, since patients in most clinical trials had ejection fractions below 30 percent, it hasn’t been clear whether patients with ejection fractions in the 30 percent to 35 percent range would benefit in the real world, he said.

“This new study of patients in clinical practice demonstrates that the benefits of implanted defibrillator therapy outweigh the risks in patients with ejection fractions of 30 to 35 percent,” Fonarow said.

The absolute difference in the death rate at three years was 8.9 percent with an implanted defibrillator for patients with ejection fractions of 30 percent to 35 percent and 10.9 percent for patients with ejection fractions of less than 30 percent. “Thus the size of the benefit was similar and large in both groups,” Fonarow said.

“While there are potential complications with implanted defibrillator therapy, the benefits in appropriately selected patients outweigh these risks, and while the therapy is costly, cost-effectiveness analyses suggest this therapy provides reasonable value,” he said.

These findings lend further support for current guideline recommendations to implant defibrillators in eligible patients with an ejection fraction of 35 percent or less, Fonarow said.

The report was published in the June 4 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association. The study was funded by the U.S. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Dr. Bryan Henry, an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Rochester Medical Center in Rochester, N.Y., said the “findings of this paper validate our current guidelines, but are also sobering.”

“The absolute benefit is much greater in those with ejection fractions of less than 30 percent than for those between 30 and 35 percent, but statistical benefit still exists,” he said.

When discussing these benefits with patients, doctors need to have an honest discussion about the magnitude of benefit, Henry said.

Even patients who have severely decreased function have to be told that, on average, 45 percent will die within three years even with an implanted defibrillator, he said.

“We are making a modest impact with our interventions, but outcomes are still sobering, and we need to continue to focus our efforts on prevention,” Henry said.

For the study, researchers studied 3,120 patients with ejection fractions of 30 percent to 35 percent, comparing deaths among those who had implanted defibrillators with those who did not.

They repeated their analysis among 4,578 patients with ejection fractions of less than 30 percent.

The researchers found that survival of heart failure patients with ejection fractions of 30 percent to 35 percent improved in those with implanted defibrillators, compared with those without them. The death rate at three years dropped from 55 percent to 51.4 percent when a defibrillator was implanted, they noted.

Implanted defibrillators were associated with even greater increases in survival among heart failure patients with ejection fractions of less than 30 percent. Among these patients, three-year death rates dropped from almost 58 percent to 45 percent with implantable defibrillator use, the researchers found.

Dr. Todd Cohen, director of the pacemaker-arrhythmia center at the Winthrop-University Hospital in Mineola, N.Y., said that an earlier study had shown improved survival with an implantable defibrillator in patients with mild to moderate congestive heart failure and an ejection fraction of less than or equal to 35 percent.

“This new study gives additional support for defibrillator implantation according to the approved guidelines,” he said.

More information

For more information on heart failure, visit the American Heart Association.

Source: HealthDay

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.