- Comparing Whey and Plant-Based Protein: Which is Best?

- How Long Does Nicotine Remain in Your System?

- The Best Time of Day to Drink Bone Broth to Maximize Health Benefits

- 8 Ways to Increase Dopamine Naturally

- 7 Best Breads for Maintaining Stable Blood Sugar

- Gelatin vs. Collagen: Which is Best for Skin, Nails, and Joints?

- The Long-Term Effects of Daily Turmeric Supplements on Liver Health

- Could Your Grocery Store Meat Be Causing Recurring UTIs?

- Are You Making This Expensive Thermostat Error This Winter?

- Recognizing the Signs of Hypothyroidism

Ethicists Grapple With Tough Questions Over Release of Ebola Drugs

As the number of dead in the West African Ebola outbreak nears 1,000, many people are calling for the wider production and release of untested medicines that might help patients.

A precious handful of samples of one such drug, called ZMapp, appeared to boost the recovery of two American aid workers stricken with the viral disease, which has a 90 percent fatality rate. And on Monday, Spain announced that it had obtained the drug for a Spanish priest who caught Ebola while in Liberia.

ZMapp had proven effective in monkeys at fighting Ebola, but it had never been tested in humans.

Responding to demands for wider access to ZMapp and other drugs in the pipeline, the World Health Organization has convened an expert panel of medical ethicists to meet later this week. That panel will inform the WHO on the pros and cons of such a decision.

“We have a disease with a high fatality rate without any proven treatment or vaccine,” Marie-Paule Kieny, WHO assistant director-general, said in a statement. “We need to ask the medical ethicists to give us guidance on what the responsible thing to do is.”

On the surface, the choice seems obvious: Why wouldn’t officials use every tool in their arsenal to combat what WHO now labels a “public health emergency”?

But ethicists say there’s a hornet’s nest of questions involved in making these largely untested drugs available to sick people.

Who would be first in line to get short-in-supply medications? Who will make that decision? How will doctors collect data on how the drugs perform? How do you communicate the risks of an experimental drug to a poorly educated inhabitant of a rural village? And would the money for these drugs be better spent on quarantine supplies and public education, to help prevent disease transmission?

“Some people look at the word ‘expedited’ as very favorable,” said Dr. Samuel Packer, chair of the ethics committee at North Shore University Hospital in Manhasset, N.Y. “Who wouldn’t want something expedited? It can be very hard to say that’s not a good thing to do. But history says a lot of time when we rush things through, people are harmed.”

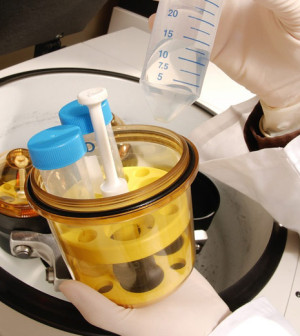

ZMapp is an antibody cocktail made by a small San Diego-based biotech firm. The two aid workers who received it, Dr. Kent Brantly and Nancy Writebol, have been evacuated to the United States and appear to be recovering, according to media reports.

Hearing the news, the Nigerian government asked the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for access to the drug, The Guardian reported. But the CDC responded that there are virtually no doses of ZMapp left, meaning that West African nations would have to wait several months for new supplies of the untested drug to be generated.

In the meantime, desperation has opened the floodgates. Other drug manufacturers have come forward to urge the use of their own untested Ebola medications.

Waiving the usual requirements of waiting for the results of rigorous clinical trials may seem appealing — particularly since Brantly and Writebol appear to have benefitted from the therapy. But have they really?

“The problem is you have no idea whether the medication worked or didn’t work,” said Dr. Ezekiel Emanuel, chair of the department of medical ethics and health policy at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine. “You can’t know after treating only two people, with a disease like this.”

Also, allowing widespread access to an untested drug doesn’t allow doctors to collect data in any meaningful way, he added. So experts will have little way of knowing if the medicine is working or not — or if it is safe.

For example, “if we’ve got a crisis and we are willing to take a higher risk and step over the animal testing, we still need to know whether the drug is effective or risky,” he reasoned.

There’s also the sticky question of choosing who of the thousands infected will get the drug. According to medical ethicist Jennifer Blumenthal-Barby, that bridge has already been crossed, in part, with the decision to give the few existing samples of ZMapp to Brantly and Writebol, rather than to any of the nearly 1,800 West Africans who have been infected by Ebola.

“One hopes that it was on the basis of sound moral reasoning and not just biased affinity for Americans by Americans,” said Blumenthal-Barby, who is assistant professor with the Center for Medical Ethics and Health Policy at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston.

“One might argue that the treatment was more likely to be effective on the Americans given the medical infrastructure and support those two patients would have here in the U.S., relative to patients in hospitals in Africa,” she said. But she added that many others would argue for equal access to anyone infected with Ebola.

“Who is going to be the body of people choosing the patients?” Packer added. “I worry about the representation of the four countries involved, for example. Are they going to be fairly represented?”

He is also concerned about how health care workers in the field in West Africa will help desperate patients understand the potential risks of an untested drug.

The outbreak has particularly affected rural parts of the four nations involved, and the people there are likely to be very unsophisticated in their knowledge of modern medicine.

“You really worry how people in a vulnerable population will understand the risks,” he said. “Do you think you can give informed consent, or are you likely to be coercive? How would I explain the risk of a brand-new drug to an African patient?”

Finally, Packer wonders whether spending millions to rush the manufacture of untested drugs is the best use of strained resources.

The same money could be used to improve still-ragged quarantine efforts in West Africa, he said. Officials could buy gloves, masks, biohazard suits and other quarantine supplies, and even pay to help educate more people there on proper quarantine procedures.

“There’s no glamor in it, but you talk to any person who knows this kind of stuff, and clearly [improvements in] public health has done more good than any drug ever developed,” Packer said.

More information

For more on Ebola, head to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Source: HealthDay

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.