- The Best Time of Day to Drink Bone Broth to Maximize Health Benefits

- 8 Ways to Increase Dopamine Naturally

- 7 Best Breads for Maintaining Stable Blood Sugar

- Gelatin vs. Collagen: Which is Best for Skin, Nails, and Joints?

- The Long-Term Effects of Daily Turmeric Supplements on Liver Health

- Could Your Grocery Store Meat Be Causing Recurring UTIs?

- Are You Making This Expensive Thermostat Error This Winter?

- Recognizing the Signs of Hypothyroidism

- 10 Strategies to Overcome Insomnia

- Could Artificial Sweeteners Be Aging the Brain Faster?

Lab-Grown Vaginas, Noses Herald New Options for Patients

Doctors have successfully implanted laboratory-grown vaginas into four teenage girls suffering from a rare birth defect, creating new organs with feel and function comparable to that of a “natural” vagina, a new study reports.

Another research team is reporting the first successful nose reconstruction surgery using laboratory-grown cartilage.

In both cases, doctors harvested the patients’ own cells and used them to create new tissue that was then grafted back onto the body.

The two studies, published online April 11 in The Lancet, show how years of research into tissue engineering for skin grafts is being put to practical use for other purposes, said Dr. Samuel Lin, an associate professor of surgery at Harvard Medical School and site director of Harvard’s plastic surgery residency training program.

“Perhaps now we’re just seeing the translational products of all that research that has been going on for years,” Lin said.

One study involved girls aged 13 to 18 who were born with Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndrome, a rare genetic condition in which the vagina and uterus are underdeveloped or absent.

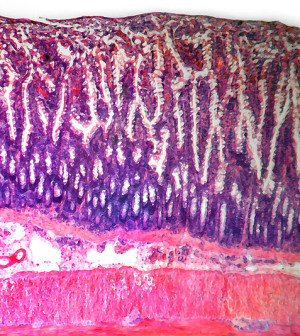

Researchers harvested muscle cells and epithelial cells from a biopsy (surgically removed tissue sample) of each girl’s genitals. Epithelial cells line body cavities and are able to generate or release fluid and detect sensation.

In a process that took three to five weeks, doctors grew the cells into larger tissue cultures that were then attached to a biodegradable “scaffold” hand-sewn into the shape of a vagina. The scaffolds were tailor-made to fit each patient and are made of the same type of material used in surgical sutures.

Once the new vaginas were ready, surgeons created a canal in each patient’s pelvis and stitched the scaffold to the girls’ reproductive structures. The girls’ bodies proceeded to form nerves and blood vessels into the grafts, and gradually replaced the engineered scaffold with a new, permanent organ.

“It’s just like when you’re having plastic surgery and they place a skin graft on you to replace damaged tissue,” said senior author Dr. Anthony Atala, director of the Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center’s Institute for Regenerative Medicine in Winston-Salem, N.C. “The graft will re-grow blood vessels and nerves,” he said.

The girls received their grafts between 2005 and 2008, and data from annual follow-up visits show that even up to eight years after the surgeries the organs had normal function.

Tissue biopsies, MRI scans and internal exams using magnification all showed that the engineered vaginas were similar in makeup and function to natural tissue. Even doctors said they couldn’t tell where the girls’ natural tissue ended and the graft began.

Questionnaires the girls completed showed they test normal in all areas of female sexual function, including desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction and painless intercourse.

The results are “fascinating” given the complexity of the tissue structure and function of a vagina, said Dr. Monica Mainigi, assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania.

“I think it’s going to open up numerous possibilities for treatment,” she said. “It’s a promising new field for medicine in general.”

Atala said this particular procedure might also help women needing vaginal reconstruction because of cancer or an injury, but the technology behind it has uses that extend beyond gynecology.

His research team also is working to grow new versions of 30 other tissues and organs, attempting to replicate body parts such as heart valves, blood vessels, and liver and kidney tissue.

“We can use this strategy to create other organs as well,” he said. “This research has allowed us to advance the technology.”

In the other study, Swiss scientists harvested nasal cartilage cells from five patients, ages 76 to 88, who had severe defects of their noses following skin cancer surgery.

During skin cancer surgery, doctors often have to cut away parts of cartilage to remove a tumor. Surgeons usually reconstruct the nose using cartilage from the person’s ear or ribs, but the procedure can be very invasive and painful.

The researchers at the University of Basel in Switzerland grew the cartilage cells into new tissue 40 times the size of the original biopsy in one month, and then used that tissue to rebuild the noses of the patients.

One year after the reconstruction, all five patients were satisfied with their ability to breathe as well as with the appearance of their nose. None reported any side effects.

Doctors from the research team said the same technology could be used to engineer cartilage for reconstruction of eyelids, ears and knees.

However, both pilot studies featured very small groups of patients. Mainigi said more patients will need to receive these grafts and be followed for years before doctors can be sure there are no long-term consequences.

More information

For more on tissue and organ engineering, visit the Wake Forest School of Medicine.

Source: HealthDay

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.