- Comparing Whey and Plant-Based Protein: Which is Best?

- How Long Does Nicotine Remain in Your System?

- The Best Time of Day to Drink Bone Broth to Maximize Health Benefits

- 8 Ways to Increase Dopamine Naturally

- 7 Best Breads for Maintaining Stable Blood Sugar

- Gelatin vs. Collagen: Which is Best for Skin, Nails, and Joints?

- The Long-Term Effects of Daily Turmeric Supplements on Liver Health

- Could Your Grocery Store Meat Be Causing Recurring UTIs?

- Are You Making This Expensive Thermostat Error This Winter?

- Recognizing the Signs of Hypothyroidism

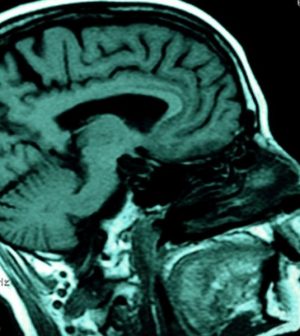

Only Spoken Words Processed in Newly Discovered Brain Region

A dementia study has led researchers to a brain region that processes spoken, not written, words.

Northwestern University researchers worked with four patients who had a rare type of dementia called primary progressive aphasia (PPA), which destroys language.

Although able to hear and speak, they could not understand what was said out loud. However, they could still process written words. For example, if they read the word “hippopotamus,” they could identify a picture of a hippo. But if someone said the word “hippopotamus,” they couldn’t point to its picture.

Through their tests with these patients, the researchers were able to identify an area in the left brain that appears specialized to process spoken words.

“We always think of these degenerative diseases as causing widespread impairment, but in early stages, we’re learning that neurodegenerative disease can be selective with which areas of the brain it attacks,” said senior author Sandra Weintraub. She’s a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and neurology at Northwestern’s Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago.

“The fact that only the auditory words were impaired in these patients and their visual words were untouched leads us to believe we’ve identified a new area of the brain where raw sound information is transformed into auditory word images,” Weintraub explained in a university news release.

Because the study included only four patients, the findings are preliminary. But the study authors said further research could improve understanding of this type of dementia and lead to therapies for it that focus on written, rather than spoken, communication.

“It’s typically very frustrating for patients with PPA and their families,” said Weintraub. “The person looks fine, they’re not limping and yet they’re a different person. It means having to readjust to this person and learning new ways to communicate.”

The study was published March 21 in the journal Cognitive and Behavioral Neurology.

More information

The National Aphasia Association has more on primary progressive aphasia.

Source: HealthDay

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.