- Comparing Whey and Plant-Based Protein: Which is Best?

- How Long Does Nicotine Remain in Your System?

- The Best Time of Day to Drink Bone Broth to Maximize Health Benefits

- 8 Ways to Increase Dopamine Naturally

- 7 Best Breads for Maintaining Stable Blood Sugar

- Gelatin vs. Collagen: Which is Best for Skin, Nails, and Joints?

- The Long-Term Effects of Daily Turmeric Supplements on Liver Health

- Could Your Grocery Store Meat Be Causing Recurring UTIs?

- Are You Making This Expensive Thermostat Error This Winter?

- Recognizing the Signs of Hypothyroidism

‘Bubble Boy’ Disease May Be More Common Than Thought

A rare birth disorder that dismantles a baby’s immune system is twice as common as once believed, a new study of more than 3 million infants says.

This is the first evaluation of the effect of screening newborns for the life-threatening but treatable condition known as severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), or “Bubble Boy” disease, the researchers noted.

“People were made aware of this condition by the boy in the bubble, who was born without an immune system,” said study author Dr. Jennifer Puck, a pediatric immunologist at Benioff Children’s Hospital at the University of California, San Francisco. She was referring to the case of David Vetter, a Texas boy born in 1971 who lived in a sterile plastic bubble until he died at age 12.

“Before there were good treatments, he had to spend his life in a germ-free environment. But since that time, there are treatments available for every baby born with this, as long as treatment can be started before they get fatal infections,” she explained.

Screening of newborns picks up the disease in time for lifesaving treatment before complications occur, Puck said. “This is the first time that a disorder of the immune system has been amenable to newborn screening,” she said.

The report was published Aug. 20 in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

“Screening for SCID has picked up a lot of cases that otherwise would not have been detected and has saved lives,” said Puck, who designed the screening test for the disease.

Before screening, the exact number of babies born with SCID wasn’t known, Puck said. “That’s a question we can answer now,” she said. “Before we just had to guess at the number of SCID cases.”

“We guessed it was one in 100,000, but this study shows it’s twice as common [one in 58,000],” Puck said. “That indicates that before screening or in the states that are still not screening, babies are being missed and they’re dying of infections because no one realized that they had a problem with their immune system,” she said.

Currently, 23 states screen for SCID, Puck said.

For the study, researchers analyzed more than 3 million infants screened for SCID in 10 states and the Navajo Nation born between January 2008 and July 2013.

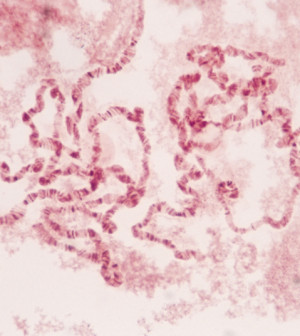

SCID is a group of disorders resulting from defects in genes that are essential for fighting infections. The condition becomes apparent in the first months after birth as immunity protection from the baby’s mother wears off.

If untreated, SCID is fatal. However, treatments that restore the baby’s immune system are available, including gene therapy or transplanting bone marrow cells from a healthy donor.

In more than 80 percent of SCID cases, there is no family history of the condition and it only comes to light as infections develop, which is why screening is so important, Puck said.

Detecting SCID allows doctors to protect the baby from infections as they begin treatment. Of the 52 babies with SCID in the study, 49 were treated with stem cell transplants or gene therapy. Three babies died before treatment began and four died after transplants. The other 45 infants survived.

Screening detects more than a dozen genetic causes of SCID, the researchers say. The test also revealed that a mutation on the X chromosome affecting boys was less common than thought. It was believed that this mutation caused half of all SCID cases, but this study found the mutation in only 19 percent of cases.

In addition, the number of SCID cases among babies without known gene defects was bigger than anticipated. It seems that there are more genes involved in SCID than thought, the researchers noted.

Dr. Neil Holtzman, a professor emeritus in the department of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore and author of an accompanying journal editorial, said that the SCID test should be done consistently throughout the country.

“Greater standardization of the newborn screening test for SCID is needed,” he said. “The test and follow-up must be conducted in a timely manner to save lives. However, newborn screening in the United States is not keeping pace with advances in technology.”

More information

Visit Boston Children’s Hospital for more on SCID.

Source: HealthDay

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.