- Comparing Whey and Plant-Based Protein: Which is Best?

- How Long Does Nicotine Remain in Your System?

- The Best Time of Day to Drink Bone Broth to Maximize Health Benefits

- 8 Ways to Increase Dopamine Naturally

- 7 Best Breads for Maintaining Stable Blood Sugar

- Gelatin vs. Collagen: Which is Best for Skin, Nails, and Joints?

- The Long-Term Effects of Daily Turmeric Supplements on Liver Health

- Could Your Grocery Store Meat Be Causing Recurring UTIs?

- Are You Making This Expensive Thermostat Error This Winter?

- Recognizing the Signs of Hypothyroidism

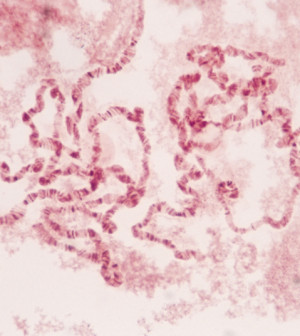

First ‘Epigenomes’ Map Highlights How Genes Spur Health, Disease

In what may be a big step forward in human biology, scientists are issuing the first comprehensive map of “human epigenomes” — the range of chemical and structural shifts that determine how genes govern health.

The new map is the result of years of work by an international consortium of researchers. Experts say the new data will help scientists better understand how genetic disruption affects a wide range of illnesses, including autism, heart disease and cancer.

“The DNA sequence of the human genome is identical in all cells of the body, but cell types such as heart, brain or skin cells have unique characteristics and are uniquely susceptible to various diseases,” researcher Joseph Costello, of the University of California, San Francisco, explained in a university news release.

He said that epigenomic factors effectively “allow cells carrying the same DNA to differentiate into the more than 200 types found in the human body.”

By mapping the mechanics behind 111 key patterns of gene expression (activation), the research team hopes it can shed light on how that differentiation process works — for either good or ill.

The long-term goal, the researchers said, is to harness this new data to find better treatments for a wide range of cancers, autoimmune disorders and other illnesses that affect critical organs, such as the heart, brain or skin.

Costello is a member of the Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center and is one of four directors of the U.S. National Institutes of Health’s Roadmap Epigenome Mapping Centers (REMC). The REMC consortium includes hundreds of researchers from the University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC), the University of Southern California (USC), and Washington University in St. Louis (WUSTL). Canadian members include both the Michael Smith Genome Sciences Centre and the University of British Columbia (UBC), both based in Vancouver, British Columbia.

The group published the new map online Feb. 18 in the journal Nature, accompanied by simultaneous publication in six other sister journals.

The entire effort began back in 2006. Since that time, REMC has focused its research on the stability and instability of chemical markers found on the spaghetti-like strands of DNA that are tucked into every human cell.

As the team explained, when everything is going well, these markers keep genes functioning as they should. However, they’re vulnerable to environmental assault — factors such as exposure to toxins, bad diets or aging — and can mutate.

When they mutate, a cell’s DNA can be activated (or fail to activate), leading to potentially harmful shifts in gene activity, the researchers said.

With such shifts comes the risk for disease.

The new epigenomic map lays out how these changes occur in several types of cells, including sperm cells, breast cells, blood cells, brain cells and skin cells.

All of the new information is being placed at the fingertips of scientists worldwide, via an online repository for all of the REMC’s published data.

The hope is that scientists working in disparate fields can dip into the databank and better coordinate and complement each other’s work.

“You’ve had cancer researchers studying the genome — the role of mutations, deletions and so on — and others studying epigenomes,” Costello said. “They’ve almost been working on parallel tracks, and they didn’t talk to each other all that much.”

However, “over the past five or six years, there’s been a reframing of the discussion,” he said. That change in focus has led researchers and drug manufacturers to better appreciate the importance of the epigenome when considering both disease risk and potential new treatments, he added.

More information

Visit the U.S. National Institutes of Health for more on the epigenome.

Source: HealthDay

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.