- Comparing Whey and Plant-Based Protein: Which is Best?

- How Long Does Nicotine Remain in Your System?

- The Best Time of Day to Drink Bone Broth to Maximize Health Benefits

- 8 Ways to Increase Dopamine Naturally

- 7 Best Breads for Maintaining Stable Blood Sugar

- Gelatin vs. Collagen: Which is Best for Skin, Nails, and Joints?

- The Long-Term Effects of Daily Turmeric Supplements on Liver Health

- Could Your Grocery Store Meat Be Causing Recurring UTIs?

- Are You Making This Expensive Thermostat Error This Winter?

- Recognizing the Signs of Hypothyroidism

One Gene Change 2 Million Years Ago Left Humans Vulnerable to Heart Attack

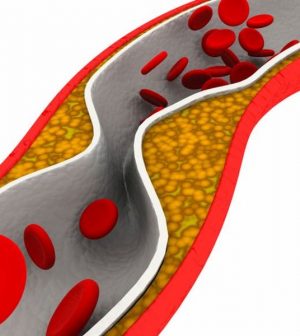

As far as scientists know, humans are the only species that get heart attacks linked to clogged arteries.

Now, new research suggests that just one DNA change occurring 2 to 3 million years ago may be to blame.

The finding might give insight into how to prevent and treat the attacks, according to researchers at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD). Already, they say, the findings implicate the consumption of red meat as a factor in heart attack risk.

One heart specialist said the findings are intriguing.

“There now seems to be a plausible link between genetics, diet, inflammation and atherosclerosis [hardening of the arteries],” said Dr. James Lafferty, who wasn’t involved in the study. “This may truly be the missing link.”

The UCSD team noted that no other species is known to suffer heart attacks due to atherosclerosis. Even chimpanzees in captivity — which, like humans, are often inactive, collect cholesterol in their blood and can have high blood pressure — don’t get heart attacks due to fat-clogged arteries.

So why humans? To find out, researchers led by professor of pathology Dr. Nissi Varki and professor of medicine Dr. Ajit Varki looked to a gene known as CMAH. The gene’s job is to produce a sialic acid sugar molecule called Neu5Gc, which in other mammals appears to greatly reduce the likelihood of atherosclerotic changes in blood vessels.

Trouble is, CMAH doesn’t function in humans — it appears to have been “switched off” by evolution millions of years ago.

The researchers theorized that this genetic event occurred because a dangerous malarial parasite recognized — and thrived– in the presence of Neu5Gc. So the human genome evolved to shut down CMAH and Neu5Gc production.

However, that meant humans became more vulnerable to fatty deposits in arteries, the Varkis and colleagues reported.

To test the theory, the UCSD team compared rates of atherosclerosis in normal mice, which have a working CMAH gene, and mice genetically tweaked to have a switched-off gene.

The result: Mice without active CMAH showed a near-doubling of fatty buildup in blood vessels.

That unhealthy activity rose even higher when mice without a working CMAH gene were fed red meat, which naturally contains Neu5Gc.

According to the researchers, that finding could explain the link between diets high in red meat and an upped risk for heart disease in humans. They believe that contact with Neu5Gc could set off an immune reaction in the human body, which in turn leads to a chronic state of inflammation in blood vessels.

“When the chemical that is missing from our bodies is ingested in the form of red meat, since other animals can still produce this, it seems to create an immune reaction, since we no longer produce it,” said Lafferty, who is chair of cardiology at Staten Island University Hospital in New York City.

But even folks who eschew meat can get heart attacks, the UCSD team noted.

All in all, the new findings “may help explain why even vegetarian humans without any other obvious cardiovascular risk factors are still very prone to heart attacks and strokes, while [humans’] other evolutionary relatives are not,” Dr. Nissi Varki said in a university news release.

Lafferty said the research may help explain an enduring medical mystery.

“As cardiologists, we are always profoundly aware that even if all risk factors do not exist humans still have reasonable chance of developing atherosclerosis,” he said.

But the study also points to new hope for patients.

“There are also some new therapies that are aimed at reducing inflammation,” Lafferty said, and these treatments “have been shown to reduce cardiac events, even in patients whose risk factors have been maximally modified.”

He believes research like the new study “will lead to filling our knowledge gaps and lead the way to new therapeutic interventions.”

The findings were published July 22 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

More information

There’s more on heart attack prevention at the American Heart Association.

Source: HealthDay

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.