- 8 Ways to Increase Dopamine Naturally

- 7 Best Breads for Maintaining Stable Blood Sugar

- Gelatin vs. Collagen: Which is Best for Skin, Nails, and Joints?

- The Long-Term Effects of Daily Turmeric Supplements on Liver Health

- Could Your Grocery Store Meat Be Causing Recurring UTIs?

- Are You Making This Expensive Thermostat Error This Winter?

- Recognizing the Signs of Hypothyroidism

- 10 Strategies to Overcome Insomnia

- Could Artificial Sweeteners Be Aging the Brain Faster?

- Techniques for Soothing Your Nervous System

Antidote Might Reverse Complication From Blood Thinner Pradaxa

Scientists say they’re close to having a treatment that can quickly reverse the effects of the anti-clotting drug Pradaxa when necessary.

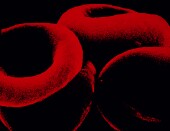

Pradaxa is a new kind of blood thinner. It was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2010 to prevent strokes caused by atrial fibrillation, a heart rhythm problem that puts people at risk for blood clots that can travel to the brain.

It’s easier for patients to take Pradaxa than the older, standard blood thinner warfarin. But unlike warfarin, there’s no way to rapidly reverse its action. That can be a life-threatening problem in emergency situations.

Doctors have reported cases of patients on Pradaxa who have died after accidents because their blood wouldn’t clot.

“There’s a perception among practitioners that they’re a little bit concerned about using these new [anti-clotting drugs] because of the lack of a reversal agent,” said Dr. Helmi Lutsep, chairwoman of the department of neurology at Oregon Health and Science University, in Portland.

Now researchers say they’ve discovered a way to block the drug.

Pradaxa works by stopping the action of the enzyme thrombin. Thrombin is key to blood clotting because it breaks a protein called fibrinogen into smaller fragments that glue platelets together, allowing a blood clot to form.

The antidote is a piece of a protein that sticks to one arm of Pradaxa’s molecule. The protein essentially handcuffs the drug, which keeps it from attaching to thrombin, allowing blood to clot again.

In an early test, researchers gave 145 healthy men intravenous drips of either the new protein or a placebo. There were no apparent side effects.

In an additional step, the researchers had some of the men take Pradaxa for four days. They then measured the time it took their blood to clot before and after several different doses of the new antidote. The protein returned clotting times to normal almost immediately after the five-minute treatment.

“It’s really exciting to see how well this drug works and what a good safety profile the drug has in this very first clinical study,” said the study’s lead author, Stephan Glund, a researcher with Boehringer Ingelheim, the drug company that makes Pradaxa.

The study was scheduled to be presented Monday at the annual meeting of the American Heart Association, in Dallas. Studies presented at medical conferences are considered preliminary since they haven’t yet been scrutinized by independent researchers as part of publication in a peer-reviewed medical journal.

Still, one expert not involved in the research said it was exciting.

“It’s a major thing,” said Dr. Michiel Coppens, a vascular medicine specialist at the Academic Medical Center, in Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

“From the very first launch of these drugs, there has been an immediate concern about what do we do if a patient [has] major bleeding,” Coppens said. “You want to get rid of the anticlotting effect as soon as possible to better control the bleeding.”

“[The antidote] isn’t vey toxic,” he added. “There isn’t any major side effect.”

But more research is needed to show that the antidote will actually help patients.

“The next step will be actually demonstrating that, for patients who come in with a major bleed with Pradaxa, this does actually improve the outcome,” Coppens said.

Study author Glund said his company plans to begin testing the antidote in patients starting in 2014.

More information

For more about the safe use of blood-thinning medications, head to the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Source: HealthDay

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.