- How Long Does Nicotine Remain in Your System?

- The Best Time of Day to Drink Bone Broth to Maximize Health Benefits

- 8 Ways to Increase Dopamine Naturally

- 7 Best Breads for Maintaining Stable Blood Sugar

- Gelatin vs. Collagen: Which is Best for Skin, Nails, and Joints?

- The Long-Term Effects of Daily Turmeric Supplements on Liver Health

- Could Your Grocery Store Meat Be Causing Recurring UTIs?

- Are You Making This Expensive Thermostat Error This Winter?

- Recognizing the Signs of Hypothyroidism

- 10 Strategies to Overcome Insomnia

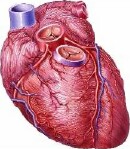

Scientists Spot How Bacterial Pneumonia Damages the Heart

Doctors have known that bacterial pneumonia can raise your risk of heart problems, but new research pinpoints why.

The bacteria actually invade and kill heart cells, increasing the chances of heart failure, abnormal heart rhythms and heart attacks in patients, scientists report.

In mice, monkeys and human heart tissue, researchers found direct evidence of heart damage caused by the bacteria, and they tried a vaccine that might one day prevent such an attack. But they also discovered that an antibiotic currently used to treat pneumonia may actually make it easier for the bacteria to damage the heart.

“When people are hospitalized for pneumonia, about 20 percent of them have something happen to their hearts, and those people are much more likely to die,” explained lead researcher Carlos Orihuela, an associate professor in the department of microbiology and immunology at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio.

“Finding out why they are having these incidents is a big deal,” he said. “We were able to show how and why that happens, and how to prevent it.”

The report was published online Sept. 18 in the journal PLOS Pathogens.

Specifically, Orihuela’s team found high levels of troponin, an indicator of heart injury, in the blood of mice with bacterial pneumonia. Moreover, the mice had abnormal heart rhythms.

When the investigators examined the hearts of the mice, they found tiny scars called microlesions, which indicate heart damage.

In these lesions, Orihuela’s group found the bacteria Streptococcus pneumoniae, which told them that bacteria were able to thrive in the hearts of mice. They also saw signs that the heart muscle next to these lesions was dying.

The researchers said that pneumolysin, a poison produced by the bacteria, was responsible for killing heart cells.

In addition, a molecule called CbpA was needed to allow the bacteria to enter the heart, they noted.

“There is a potential vaccine,” Orihuela said. But how broadly it would be used isn’t clear, he said. “We have to work on that,” he added.

The researchers tried the experimental vaccine, which was made up of CbpA and a non-toxic type of pneumolysin. In the mice, it made antibodies that prevented the bacteria from damaging the heart, Orihuela said.

The researchers next looked at heart tissue from monkeys that had been treated with antibiotics but still died from bacterial pneumonia. The investigators found microlesions, but no trace of the bacteria.

This was also the case in samples of human heart tissue taken from people who also had been treated with antibiotics but still succumbed to the disease. Two of the nine samples had microlesions, but no bacteria.

To see if antibiotics might have had a damaging effect on the heart, Orihuela’s team infected mice with bacterial pneumonia and gave them high doses of the antibiotic ampicillin when heart lesions appeared.

The mouse hearts showed the same degree of damage as the monkey and human heart tissue had shown, even though the bacteria had been killed.

Orihuela said that ampicillin caused the bacteria to “pop open,” releasing pneumolysin as it destroyed the bacteria. This could explain the heart damage, as the poison is then released directly into the heart, he said.

“There are other kinds of antibiotics — so-called bacteriostatics. Those kill the bacteria, but they don’t cause the bacteria to pop — maybe those are better,” Orihuela said.

Dr. Gregg Fonarow, a professor of cardiology at the University of California, Los Angeles, said earlier studies have shown that patients with pneumonia have a higher risk of developing heart failure and other types of heart problems.

There have been a number of mechanisms suggested that may account for this, he said. “This new study finds that a common bacteria that causes pneumonia can lead to microscopic bacteria-filled lesions within the heart,” Fonarow said.

“This microlesion formation and subsequent heart muscle damage may provide a viable explanation for why pneumonia can lead to heart failure and other heart problems,” he said.

More information

Visit the American Lung Association for more on pneumonia.

Source: HealthDay

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.