- How Long Does Nicotine Remain in Your System?

- The Best Time of Day to Drink Bone Broth to Maximize Health Benefits

- 8 Ways to Increase Dopamine Naturally

- 7 Best Breads for Maintaining Stable Blood Sugar

- Gelatin vs. Collagen: Which is Best for Skin, Nails, and Joints?

- The Long-Term Effects of Daily Turmeric Supplements on Liver Health

- Could Your Grocery Store Meat Be Causing Recurring UTIs?

- Are You Making This Expensive Thermostat Error This Winter?

- Recognizing the Signs of Hypothyroidism

- 10 Strategies to Overcome Insomnia

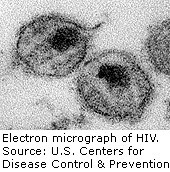

2nd Baby ‘Cured’ of HIV Suffers Relapse

An Italian toddler thought cured of HIV with early aggressive treatment following birth has suffered a relapse, his doctors report.

The 3-year-old child’s viral levels of HIV rebounded two weeks after doctors took him off antiretroviral medications, according to a case report published Oct. 4 in The Lancet.

The child’s HIV levels had been undetectable since he was 6 months old, thanks to aggressive drug therapy that doctors started within 12 hours of his birth, doctors said.

This is the second time that a child believed “cured” of HIV with early treatment has suffered a relapse once they stopped taking antiretroviral medication.

In July, a 4-year-old Mississippi girl relapsed after living HIV-free for more than two years without medication.

“What we’ve learned here is if you have an HIV-infected child who started treatment early, the fact that you have negative tests does not signify that the child has been cured or that they can be taken off treatment,” said Dr. Deborah Persaud. She is a professor of infectious diseases at the John Hopkins Children’s Center in Baltimore and one of the two pediatric HIV experts involved in the ongoing analysis of the Mississippi case.

The Italian boy, known as the “Milan baby,” was born to an HIV-positive mother in December 2009.

He was born with a heavy HIV viral load, and doctors immediately put him on antiretroviral therapy. His HIV levels immediately began to drop, and were undetectable at 6 months of age.

Tests at age 3 to measure the amount of HIV in the child’s blood suggested that the virus had been eradicated, and even antibodies to HIV had disappeared. With the agreement of the child’s mother, doctors took him off his medication regimen.

Unfortunately, the virus had been hiding in reservoirs deep in the child’s immune system, and immediately rebounded, the researchers said.

The cases highlight the difficulty of eliminating HIV from deep within the immune system.

The virus infects the “memory cells” of the immune system — cells that lie dormant deep within the system and retain the knowledge of how to respond to different types of infection, Persaud said. These cells wait in reserve, ready to be called upon to fight off a future illness.

Because these cells are dormant, drug treatments that rid the bloodstream of HIV are not able to get inside them and kill off the virus hiding within, she explained. And once antiretroviral treatment stops, any immune response that activates these memory cells will cause the patient’s HIV to re-emerge.

“It takes advantage of the very biology we use to cope with infections,” said Dr. Bruce Hirsch, an infectious diseases specialist at North Shore University Hospital in Manhasset, N.Y.

Despite these setbacks, doctors have not given up on a “functional cure” for children born with HIV.

Hirsch noted that HIV therapy given to an infected mother prior to birth has been shown to prevent transmission of the virus to her newborn.

“Because of that, I think it’s possible there may be some potential to prevent HIV infection in the first place after exposure with early therapies,” he said.

A clinical trial is moving forward to examine treatment of HIV-positive babies within the first 48 hours of life, using a drug combination similar to that administered to the Mississippi baby, Persaud said.

Dr. Michael Horberg, director of HIV/AIDS for Kaiser Permanente, agreed there is still merit to the strategy of aggressive early treatment for HIV-born infants.

“I think we will find a functional cure. We just haven’t found it yet,” Horberg said. “That doesn’t mean the principles of a strategy of hitting hard for an extended period should not work.”

At the same time, doctors should not become too hung up on the promise of a cure, when current drug therapies are as successful at controlling HIV infection as blood pressure medications are at controlling blood pressure, Hirsch said.

“Our treatments are very well-tolerated, and I think we should avoid cures that are worse than the treated disease itself,” he said.

More information

Visit the U.S. National Institutes of Health for more on HIV.

Source: HealthDay

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.