- Comparing Whey and Plant-Based Protein: Which is Best?

- How Long Does Nicotine Remain in Your System?

- The Best Time of Day to Drink Bone Broth to Maximize Health Benefits

- 8 Ways to Increase Dopamine Naturally

- 7 Best Breads for Maintaining Stable Blood Sugar

- Gelatin vs. Collagen: Which is Best for Skin, Nails, and Joints?

- The Long-Term Effects of Daily Turmeric Supplements on Liver Health

- Could Your Grocery Store Meat Be Causing Recurring UTIs?

- Are You Making This Expensive Thermostat Error This Winter?

- Recognizing the Signs of Hypothyroidism

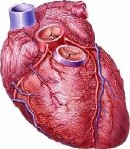

Implanted Device May Improve Hard-to-Treat Chest Pain

A stent-like device placed in a heart vein may bring relief to some people with otherwise untreatable cases of angina, a small clinical trial finds.

The study, published in the Feb. 5 New England Journal of Medicine, included 104 patients with severe angina that had eluded conventional therapies — in what doctors call “refractory” angina.

Angina refers to chronic chest pain, fatigue and breathing problems caused by atherosclerosis — a hardening and narrowing of arteries supplying blood to the heart. Usually, the symptoms can be treated with lifestyle changes, medications, or procedures that open up the narrowed arteries and improve blood flow.

But when the standard treatments don’t work, patients are out of options, said Dr. Shmuel Banai, the senior researcher on the new study and director of interventional cardiology at Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center in Israel.

Those patients often continue to have debilitating symptoms that keep them from climbing stairs or even walking more than 100 feet, Banai said.

The device his team studied, called the Reducer, is already approved in Europe but not yet in the United States. It is similar to a stent, the scaffold-like device that doctors commonly implant to prop open clogged heart arteries. But the Reducer has an hourglass shape, and instead of being placed in an artery, it’s implanted in a large heart vein, to alter the flow of blood out of the heart.

That helps keep more oxygen-rich blood circulating in the parts of the heart muscle that need it, according to Neovasc, the company that markets the device and funded the new research.

For the study, Banai’s team recruited 104 patients with class 3 or 4 angina who’d failed to improve with medication and could not have the standard invasive procedures — namely, traditional stents or bypass surgery. The classes, on a scale from 1 to 4, rate lower to greater activity limitations due to angina.

His team randomly assigned half of the patients to have the Reducer device implanted, which involves threading a catheter into the heart vein under local anesthesia. The rest of the patients were assigned to a “sham” procedure, in which the catheter was inserted but no device was implanted.

Over the next six months, 35 percent of patients with the device saw their symptoms improve by at least two “angina classes” — which is considered substantial in real-life terms, according to Banai. That compared with 15 percent of the sham-treatment group.

Other patients got relief, too. In all, 71 percent of those with the device improved by at least one angina class, versus 42 percent of the sham group.

“For these patients who are very limited in their daily activities, even one class improvement is important, and a two-class improvement is critically important,” Banai said.

One patient who received the implant suffered a heart attack soon after the procedure. But in general, the treatment appears relatively safe, according to Banai.

A cardiologist not involved in the study called it “good news for patients.”

“This condition is fairly common, and can be debilitating,” said Dr. Christopher Granger, director of the Cardiac Care Unit at Duke University Medical Center in Durham, N.C.

It’s been estimated that refractory angina affects up to 2 million people in the United States, according to Granger, who cowrote an editorial published with the study.

Still, larger and longer-term studies are needed, Granger stressed. “This is a well-done study, and it’s an important study,” he said. “But it’s still a small study.”

So far, the device seems “well-tolerated,” Granger noted. But there are, as with any medical implant, safety concerns, he said.

“There can be complications when the device is implanted, such as bleeding or infection,” Granger said. And if the device were to become blocked, that could affect the outflow of blood from the heart muscle.

What about all the patients in the sham group who also saw improvement? Granger said that could be related to the normal fluctuations in angina symptoms. Patients are enrolled in a trial when their symptoms are at their worst, and then there’s a natural wane.

But he said there could also be a “placebo effect” at work. “That means there are real physiologic changes, based on the mind’s effects on the body,” Granger said.

For now, he said, the best thing most people can do is to take steps to prevent angina, or keep it from worsening. That includes not smoking, eating a healthy diet, and keeping blood pressure and cholesterol down — with medications, if needed.

More information

The U.S. National Institutes of Health has more on preventing and treating angina.

Source: HealthDay

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.