- 8 Ways to Increase Dopamine Naturally

- 7 Best Breads for Maintaining Stable Blood Sugar

- Gelatin vs. Collagen: Which is Best for Skin, Nails, and Joints?

- The Long-Term Effects of Daily Turmeric Supplements on Liver Health

- Could Your Grocery Store Meat Be Causing Recurring UTIs?

- Are You Making This Expensive Thermostat Error This Winter?

- Recognizing the Signs of Hypothyroidism

- 10 Strategies to Overcome Insomnia

- Could Artificial Sweeteners Be Aging the Brain Faster?

- Techniques for Soothing Your Nervous System

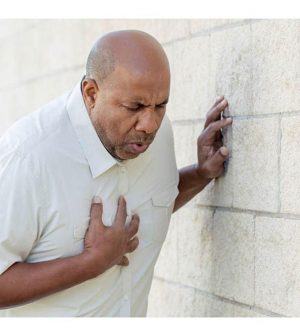

Lower Incomes May Mean Lower Survival After Heart Attack

If you’re poor and have a severe type of heart attack, the chance you’ll live through it is significantly lower than that of someone with more money, new research shows.

The finding underscores the need to close a divide in health care that hits low-income people hard, said lead researcher Dr. Abdul Mannan Khan Minhas, a hospitalist at the Hattiesburg Clinic Hospital Care Service in Mississippi.

“A lot of work is being done in this area, but obviously, as has been shown in multiple studies, a lot more needs to be done,” he said.

The type of heart attack his team studied is an ST-elevation myocardial infarction, also known as STEMI.

STEMI, which mainly affects the heart’s lower chambers, can be more severe and dangerous than other types of heart attacks.

For the study, the researchers analyzed a database of U.S. adults who were diagnosed with STEMI between 2016 and 2018, dividing patients by ZIP code to gauge household income. They also created models that helped to compare patient outcomes.

In all, there were 639,300 STEMI hospitalizations — about 35% of patients were in the lowest income category. About 19% were in the top income group.

The poorest patients had the highest death rate from all causes — 11.8%, compared to 10.4% for those in the top income group, the study found. They also had longer hospital stays and more invasive mechanical ventilation.

But the amount of money spent on their care was less — about $26,503 versus $30,540 for the top-income group, the researchers reported.

Though they were more likely to die, poor patients were, on average, almost two years younger than their affluent counterparts (63.5 years versus 65.7).

They were also more likely to be women, and to be Black, Hispanic or Native American. Most importantly, they had more than one disease or condition.

“They were more sick to begin with,” Minhas said. “For instance, these patients had more chronic lung disease, more [high blood pressure], more diabetes, more heart failure, more alcohol/drug/tobacco abuse, and more history of previous stroke as compared to the other group of patients. That’s probably the most important factor that they could think is probably contributing to this disparity.”

At the same time, these lower-income patients were also less likely to have health insurance.

Previous studies have shown that social factors have a big impact on disease outcomes. These so-called social determinants of health are “the conditions in the environments where people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship and age,” according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. They can include such things as availability of safe housing, racism, job opportunities, access to healthy foods, air quality and income.

Lower economic status has been linked to worse clinical outcomes from heart disease, as well as to having other health conditions.

Dr. Triston Smith, medical director of the cardiovascular service at the Trinity Health System in Steubenville, Ohio, reviewed the findings.

“The first impression I got is that it’s a stunning indictment of the health care system that we have, where these inequalities exist and make life and death situations simply based on one’s income and on one’s ZIP code,” he said. “I think there’s a lot to unpack here, but on face value, this does not look good for the way we provide care for our patients with heart attacks.”

Several factors probably contribute to these results, Smith said. For one, poor patients tend to be disadvantaged over their lifetimes due to co-existing conditions, he pointed out.

Even if individuals in each group have some of the same medical conditions, such as diabetes, those who are poorer may not be able to afford the medications to control the condition, Smith said.

“The other issue that I saw here and which was very concerning to me was the cost of care that was provided,” Smith said. Though the poorest patients had higher death rates, less was spent on their care.

“That’s a paradox that we need to dig into because, are we compromising the care of the patients in the lower socioeconomic groups by offering them less-effective therapies?” Smith said.

The findings were presented Wednesday at a meeting in Atlanta of the Society of Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. An abstract was previously published in the Journal of the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions.

Findings presented at meetings are considered preliminary until published in a peer-reviewed journal.

Study author Minhas said policy and public health efforts are needed to solve the problem.

“They should be directed to mitigate these inequalities and focused public health interventions should address the socioeconomic disparities,” he said.

In addition, research should explore these differences in access to care.

“We should have more prospective population-based studies and more robust study designs that help us interrogate and study these effects of social economic disparities — like income and education and all other things — on cardiovascular outcomes,” Minhas said.

More information

The American Heart Association has more on heart attacks.

SOURCES: Abdul Mannan Khan Minhas, MD, hospitalist, Hattiesburg Clinic Hospital Care Service, Hattiesburg, Miss.; Triston Smith, MD, medical director, cardiology, East Ohio Regional Hospital, Martins Ferry, Ohio; abstract only, Journal of the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, May 1, 2022; Society of Cardiovascular Angiography meeting, May 18, 2022

Source: HealthDay

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.