- The Best Time of Day to Drink Bone Broth to Maximize Health Benefits

- 8 Ways to Increase Dopamine Naturally

- 7 Best Breads for Maintaining Stable Blood Sugar

- Gelatin vs. Collagen: Which is Best for Skin, Nails, and Joints?

- The Long-Term Effects of Daily Turmeric Supplements on Liver Health

- Could Your Grocery Store Meat Be Causing Recurring UTIs?

- Are You Making This Expensive Thermostat Error This Winter?

- Recognizing the Signs of Hypothyroidism

- 10 Strategies to Overcome Insomnia

- Could Artificial Sweeteners Be Aging the Brain Faster?

Stroke Risk Spikes Shortly After Shingles Episode: Study

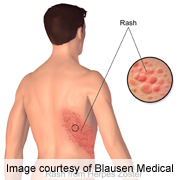

People with shingles face a significantly increased risk of stroke in the weeks following the first signs of the painful skin rash, new research suggests.

Patients’ overall stroke risk is highest in the first month after the onset of shingles, when they are 63 percent more likely to have a stroke, said study author Dr. Sinead Langan, a senior lecturer at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. The risk tapers off during the following five months, she added.

Shingles patients also have a threefold increased risk of stroke if they develop the rash around one or both eyes, according to the report published online April 3 in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases.

However, the study also delivered some good news for people with shingles, Langan added.

“We found that the risk of stroke was lower in people who were treated with antiviral medications for their shingles, compared with those not treated with antivirals,” she said. “That hasn’t been shown before, that treating with antivirals might make a difference.”

The study didn’t prove that shingles causes a stroke; it only found an association between the viral infection and stroke risk.

The apparent role of shingles in stroke is a little-known phenomenon that will emerge as a major health issue in coming years, said Dr. Maria Nagel, an assistant professor of neurology at the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

Shingles (herpes zoster) is caused by the same virus that produces chicken pox. The virus lies dormant in people’s bodies for decades, and when they are older it reactivates and produces shingles.

“More than 95 percent of the world population is infected with this virus, and by the age of 85 about 50 percent of the population would have reactivated the virus and gotten a rash,” said Nagel, who co-wrote an editorial that accompanied Langan’s study.

An estimated 1 million adults in the United States suffer from shingles every year, according to background information in the study.

There are a couple of ways that the shingles virus may raise the risk of a stroke, Langan and Nagel explained.

The virus can invade the walls of blood vessels, infecting the cells and increasing the chance that a vessel could clog or rupture, Nagel said.

That’s likely the reason why stroke risk is so pronounced in people with shingles around their eyes — from that location, the reactivated virus has a direct pathway into the arteries of the brain, she said.

Shingles also promotes inflammation in the body, which can cause arterial plaques to rupture and induce a stroke.

The new study involved 6,584 stroke victims who also suffered from shingles, drawing from a database of information of patients in over 600 general practices in the United Kingdom.

Researchers compared the risk of stroke in the time period after the patient had shingles to earlier times when the patient did not have shingles.

The investigators found the stroke rate was 63 percent higher in the first four weeks after a shingles episode compared to the patient’s baseline risk. The risk then diminished slowly over time, dropping to 42 percent in weeks 5 through 12 and then to 23 percent for up to 6 months later.

Treatment with oral antiviral medication significantly reduced this risk, the results showed. Researchers found that shingles patients who were not treated with antivirals had nearly double the stroke risk of those who received the medication.

Dr. Larry Goldstein, director of the Duke University Stroke Center, said people who have contracted shingles should talk with their doctor about going on an antiviral medication.

“If somebody has an outbreak, there’s no downside to seeking antiviral treatment,” said Goldstein, who’s also a spokesman for the American Heart Association.

Langan and Nagel both hope the findings will help promote vaccination for shingles among seniors.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that everyone 60 or older get the vaccine. It is covered by Medicare’s prescription drug plan, and most private plans also cover the shot.

“One-third of patients who get stroke from varicella zoster virus do not get a shingles rash,” Nagel said. “We can prevent those strokes by getting people vaccinated.”

More information

Visit the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for more about shingles.

Source: HealthDay

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.