- Comparing Whey and Plant-Based Protein: Which is Best?

- How Long Does Nicotine Remain in Your System?

- The Best Time of Day to Drink Bone Broth to Maximize Health Benefits

- 8 Ways to Increase Dopamine Naturally

- 7 Best Breads for Maintaining Stable Blood Sugar

- Gelatin vs. Collagen: Which is Best for Skin, Nails, and Joints?

- The Long-Term Effects of Daily Turmeric Supplements on Liver Health

- Could Your Grocery Store Meat Be Causing Recurring UTIs?

- Are You Making This Expensive Thermostat Error This Winter?

- Recognizing the Signs of Hypothyroidism

Transplant From Incompatible Living Donor Boosts Kidney Patients’ Survival

In what experts call a possible “paradigm shift,” a new study shows kidney disease patients may live far longer if they receive a transplant from an incompatible living donor rather than wait for a good match.

The findings could offer another choice for kidney patients who might otherwise die waiting for a compatible deceased donor.

Specifically, experts said the results offer hope to “highly sensitized” transplant candidates.

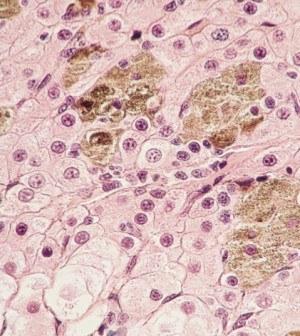

That refers to patients who have a large number of immune system antibodies ready to attack a donor organ. It’s common among people who’ve had a prior kidney transplant, according to the United Network for Organ Sharing. Patients who have had multiple blood transfusions while on dialysis, or who have been pregnant several times, can also become sensitized.

Finding a compatible donor for sensitized patients is “nearly impossible,” said study lead researcher Dr. Dorry Segev, an associate professor of surgery at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, in Baltimore.

An alternative is to transplant a kidney from an incompatible donor, with the help of special “desensitization” therapies that reduce the risk of an immune system attack on the donor organ.

Johns Hopkins pioneered the approach 15 years ago, and other transplant centers have followed suit.

Only now, though, is the long-term benefit becoming clear. Using data from 22 U.S. hospitals, Segev’s team found that more than three-quarters of patients who received a kidney from an incompatible living donor were still alive eight years later.

“This is potentially a paradigm shift,” said Dr. Michael Flessner, a program director in the division of kidney, urologic and hematologic diseases at the U.S. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, which funded the study.

Flessner expects incompatible living-donor transplants will become standard practice.

Such donations are not a panacea: There is a higher risk of rejection than with transplants from compatible living donors, said Dr. Harold Helderman, a professor of medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, in Nashville.

And because patients receive especially powerful immune-system suppressing drugs, they can be at increased risk for infections, he noted.

“But these results show that at the end of the day, these patients have a longer lifespan,” Helderman said. “So, you accept that there are risks.”

For the study, Segev’s team followed just over 1,000 sensitized patients who received a kidney from an incompatible donor at one of 22 transplant centers in the United States. They compared the patients’ survival with that of two “control” groups: slightly over 5,000 patients on the transplant waiting list who eventually received a kidney; and roughly the same number of wait-list patients who had to remain on dialysis.

After eight years, more than 76 percent of the incompatible-donor patients were still alive. That compared with 44 percent of dialysis patients and 63 percent of those who ultimately received a deceased-donor organ.

The findings were published March 10 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

An incompatible transplant is no easy process. To be desensitized, patients need a procedure called plasmapheresis, which clears the blood of antibodies that could attack the donor organ. Afterward, they receive immune-suppressing drugs aimed at preventing an antibody re-emergence.

Plasmapheresis has to be repeated several times before the transplant — and often afterward as well, Flessner noted.

The desensitization process also adds about $20,000 to $30,000 to the cost of getting a transplant, according to the University of Wisconsin’s transplant center, one of the U.S. programs that performs the procedure.

But it’s still far cheaper than dialysis in the long run, Segev said in a news release from Johns Hopkins.

Right now, just over 100,000 Americans are on the waiting list for a donor kidney, according to the National Kidney Foundation. Segev and his team estimate that 32,000 of them are sensitized.

When those patients have a willing, but incompatible, living donor, Segev said, it may be in their “best interests” to have the transplant rather than wait.

Flessner agreed. “This holds out the hope of more family members being able to give this great gift,” he said. “And it really is the gift of life.”

More information

The National Kidney Foundation has more on kidney transplantation.

Source: HealthDay

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.