- How Long Does Nicotine Remain in Your System?

- The Best Time of Day to Drink Bone Broth to Maximize Health Benefits

- 8 Ways to Increase Dopamine Naturally

- 7 Best Breads for Maintaining Stable Blood Sugar

- Gelatin vs. Collagen: Which is Best for Skin, Nails, and Joints?

- The Long-Term Effects of Daily Turmeric Supplements on Liver Health

- Could Your Grocery Store Meat Be Causing Recurring UTIs?

- Are You Making This Expensive Thermostat Error This Winter?

- Recognizing the Signs of Hypothyroidism

- 10 Strategies to Overcome Insomnia

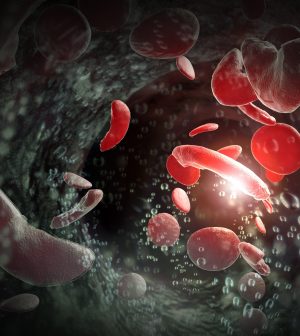

FDA Advisors Say New Gene Therapy for Sickle Cell Disease is Safe

WEDNESDAY, Nov. 1, 2023 A new gene therapy for sickle cell disease was deemed safe by a U.S. Food and Drug Administration advisory panel on Tuesday, paving the way for full approval by early December.

The FDA had already decided that the therapy, known as exa-cel, was effective.

Developed by Vertex Pharmaceuticals of Boston and CRISPR Therapeutics of Switzerland, exa-cel frees patients from the excruciating symptoms of sickle cell disease. If approved by Dec. 8, as expected, it would become the first medicine to treat a genetic disease with the CRISPR gene-editing technique, CRISPR Therapeutics said in a news release.

But it won’t be the only new treatment for the inherited condition coming down the pike: By Dec. 20, the FDA will also decide on a second potential cure for a disease that typically strikes Black people, a gene therapy crafted by Bluebird Bio, of Somerville, Mass.

“We are finally at a spot where we can envision broadly available cures for sickle cell disease,” said Dr. John Tisdale, director of the cellular and molecular therapeutics branch at the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute and a member of the advisory committee, the New York Times reported.

In the case of exa-cel, the one-time treatment permanently changes DNA in a patient’s blood cells.

How does it work? Stem cells are removed from a patient’s blood, and then CRISPR gene-editing technology knocks out a gene that triggers the development of defective, crescent-shaped blood cells. Meanwhile, medicine kills off flawed blood-producing cells in patients, who are then given back their own altered stem cells.

“Anything that can help relieve somebody with this condition of the pain and the multiple health complications is amazing,” Dr. Allison King, a professor at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, told the Associated Press recently. “It’s horribly painful. Some people will say it’s like being stabbed all over.”

In briefing documents filed with the advisory committee before the meeting, Vertex said that 46 people got the treatment in its study. Among the 30 who had 18 months of follow-up, 29 were free of pain crises for at least a year and all 30 avoided being hospitalized for pain crises.

Vertex has said it plans to follow clinical trial patients for 15 years, and the advisory committee members said they saw no reason to delay approval of the treatment.

There can always be additional studies, noted committee member Alexis Komor, a professor of chemistry and biochemistry at the University of California, San Diego, the Times reported. But that would be “expecting perfection at the expense of progress,” she said.

Victoria Gray, who has received the gene therapy, shared her experience with researchers at a scientific conference recently, saying she felt she “was being reborn” when she got the therapy, the AP reported. Gray had experienced bouts of terrible pain since childhood.

Now, she is active with her kids and works full time.

“My children no longer have a fear of losing their mom to sickle cell disease,” she said.

Sickle cell disease affects the protein that carries oxygen in red blood cells. The cells can become crescent-shaped because of a genetic mutation. This can block blood flow and cause pain, organ damage and stroke. The disease affects millions of people around the world.

It occurs more often in places where malaria is common, like Africa and India. Being a carrier of the trait may protect against severe malaria.

Standard treatments include medications and blood transfusions. A bone marrow transplant from a closely matched donor without the disease is the only cure.

The second gene therapy for sickle cell disease that the FDA will consider is intended to work by making functional copies of a modified gene, the AP reported. This helps red blood cells produce hemoglobin that isn’t misshapen.

Prices for the two gene therapies haven’t been released.

However, a price tag of around $2 million would be considered cost-effective because the existing treatments cost about $1.6 million for women and $1.7 million for men from birth to age 65, according to recent research.

“But if you think about it,” King said, “how much is it worth for someone to feel better and not be in pain and not be in the hospital all the time.”

More information

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has more on sickle cell disease.

SOURCE: New York Times; Associated Press

Source: HealthDay

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.