- Recognizing the Signs of Hypothyroidism

- 10 Strategies to Overcome Insomnia

- Could Artificial Sweeteners Be Aging the Brain Faster?

- Techniques for Soothing Your Nervous System

- Does the Water in Your House Smell Funny? Here’s Why

- Can a Daily Dose of Apple Cider Vinegar Actually Aid Weight Loss?

- 6 Health Beverages That Can Actually Spike Your Blood Sugar

- Treatment Options for Social Anxiety Disorder

- Understanding the Connection Between Anxiety and Depression

- How Daily Prunes Can Influence Cholesterol and Inflammation

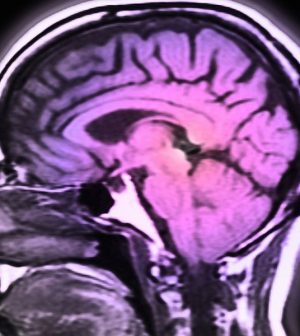

‘Zombie Genes’ Spur Some Brain Cells to Grow Even After Death

When people die some cells in their brains go on for hours, even getting more active and growing to gargantuan proportions, new research shows.

Awareness of this activity, spurred on by “zombie genes,” could affect research into diseases that affect the brain.

For the study, researchers analyzed gene expression using fresh brain tissue collected during routine surgery and found that, in some cells, gene expression increased after death. The investigators observed that inflammatory glial cells grew and sprouted long arm-like appendages for many hours after death.

“Most studies assume that everything in the brain stops when the heart stops beating, but this is not so,” said corresponding author Dr. Jeffrey Loeb. He is head of neurology and rehabilitation at the University of Illinois Chicago College of Medicine.

Gene expression is the process by which the instructions in DNA are converted into instructions for making proteins or other molecules, according to Yourgenome.org.

“That glial cells enlarge after death isn’t too surprising given that they are inflammatory and their job is to clean things up after brain injuries like oxygen deprivation or stroke,” Loeb said in a university news release.

The implications are significant, he added.

Most research that uses human brain tissues after death to find treatments and potential cures for disorders (such as autism, schizophrenia and Alzheimer’s disease) do not account for continued gene expression or cell activity.

“Our findings will be needed to interpret research on human brain tissues,” Loeb said. “We just haven’t quantified these changes until now.”

Loeb is director of the UI NeuroRepository, a bank that stores brain tissues, with consent, from patients with neurological disorders. The tissue is collected and stored either after patients die or during surgery. Not all of the tissue is needed for disease diagnosis, so some can be used for research.

Loeb and his team noticed that patterns of gene expression in fresh brain tissue didn’t match any published findings of gene expression in tissue analyzed after death.

So they conducted a simulated experiment looking at the expression of all human genes immediately after death up to 24 hours later.

About 80% of genes analyzed remained relatively stable for 24 hours. These included genes that provide basic cellular functions. Another group of genes involved in brain activity (such as memory, thinking and seizure activity) rapidly degraded in the hours after death.

A third group of genes — the “zombie genes” — got more active as the other genes slowed down. These changes peaked at 12 hours.

Loeb said the findings mean researchers need to take these changes into account, and reduce the time between death and study as much as possible to limit the magnitude of these changes.

“The good news from our findings is that we now know which genes and cell types are stable, which degrade, and which increase over time so that results from postmortem brain studies can be better understood,” he said.

The findings were published March 23 in the journal Scientific Reports.

More information

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Healthy Brain Initiative has more about Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias.

SOURCE: University of Illinois Chicago, news release, March 23, 2021

Source: HealthDay

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.