- Could Your Grocery Store Meat Be Causing Recurring UTIs?

- Are You Making This Expensive Thermostat Error This Winter?

- Recognizing the Signs of Hypothyroidism

- 10 Strategies to Overcome Insomnia

- Could Artificial Sweeteners Be Aging the Brain Faster?

- Techniques for Soothing Your Nervous System

- Does the Water in Your House Smell Funny? Here’s Why

- Can a Daily Dose of Apple Cider Vinegar Actually Aid Weight Loss?

- 6 Health Beverages That Can Actually Spike Your Blood Sugar

- Treatment Options for Social Anxiety Disorder

New Immune-Focused Therapy Shrinks Aggressive Brain Tumors

Delivering dual-targeted, immune-focused CAR T cancer therapy via a patient’s spinal fluid quickly shrank deadly brain tumors, researchers report.

CAR T therapy harnesses the power of the patient’s immune system T-cells, which are reprogrammed to seek and destroy a specific protein found on cancer cells.

However, in the new trial — focused on patients with deadly glioblastomas (GBMs) — CAR T focused on two protein targets, giving tumor cells even fewer places to hide.

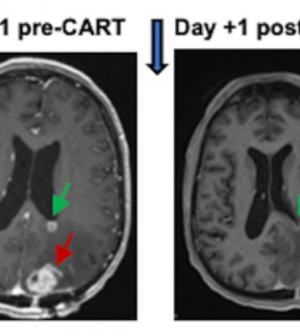

MRI brain scans of all six patients enrolled in the trial showed rapid tumor reductions occurring within a day or two of treatment.

In some cases, those reductions have continued for months, said the team from the University of Pennsylvania.

“We are energized by these results, and are eager to continue our trial, which will give us a better understanding of how this dual-target CAR T cell therapy affects a wider range of individuals with recurrent GBM,” said Dr. Donald O’Rourke, whose lab at UPenn developed the technology.

Glioblastomas are the most common and most aggressive forms of adult brain tumors, with an expected life span after diagnosis of just 12 to 18 months.

Certain treatments — surgery, radiation and chemotherapy — might beat back the tumor for a while, but recurrence is common and when that happens, death typically comes within a year.

CAR T therapy has long been used successfully to fight blood malignancies, the researchers noted, but solid tumors have been much tougher targets.

“The challenge with GBM and other solid tumors is tumor heterogeneity, meaning not all cells within a GBM tumor are the same or have the same antigen that a CAR T cell is engineered to attack,” lead investigator Dr. Stephen Bagley explained in a UPenn news release. “Every person’s GBM is unique to them, so a treatment that works for one patient might not be as effective for another.”

He added that glioblastomas are also adept at evading immune system cells — even the reprogrammed cells that are used in CAR T.

“Our challenge is getting our treatment around the tumor’s defenses so we can kill it,” said Bagley, an assistant professor of hematology-oncology and neurosurgery at UPenn.

In the new trial, Bagley, O’Rourke and colleagues decided to limit the tumor’s chances of escape by targeting two proteins on the tumor cells: Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), thought to be present in 60 percent of all glioblastomas; and interleukin-13 receptor alpha 2 (IL13Rα2), which is found in over 75 percent of these tumors.

They also crafted a way of ensuring that the CAR T cells made their way directly to the brain.

Instead of delivering them via an IV drip, as is usual, the team injected them into each patient’s spinal fluid, which travels directly to the brain.

The strategy seemed to work: MRI scans taken just 24 and 48 hours after CAR T delivery showed a remarkable shrinkage of tumors.

“These reductions have been sustained out to several months later in a subset of patients,” the UPenn researchers said.

Of course, every treatment can have side effects, and CAR T can kill healthy brain cells as well — something called neurotoxicity. According to the researchers, “substantial” neurotoxicity did occur, but it was manageable for patients.

The findings were published March 13 in the journal Nature Medicine.

O’Rourke stressed that more research is needed to confirm and optimize the success of the treatment.

“This cancer is unique in each individual, so a wider range of patients will help us determine the optimal dose, better understand effects like neurotoxicity and more firmly establish efficacy,” he said.

More information

Find out more about glioblastomas at the American Cancer Society.

SOURCE: University of Pennsylvania, news release, March 13, 2024

Source: HealthDay

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.