- Could Your Grocery Store Meat Be Causing Recurring UTIs?

- Are You Making This Expensive Thermostat Error This Winter?

- Recognizing the Signs of Hypothyroidism

- 10 Strategies to Overcome Insomnia

- Could Artificial Sweeteners Be Aging the Brain Faster?

- Techniques for Soothing Your Nervous System

- Does the Water in Your House Smell Funny? Here’s Why

- Can a Daily Dose of Apple Cider Vinegar Actually Aid Weight Loss?

- 6 Health Beverages That Can Actually Spike Your Blood Sugar

- Treatment Options for Social Anxiety Disorder

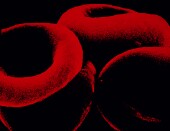

Manual Clot Removal After Heart Attack May Not Help, Could Harm

A new study calls into question the value of removing blood clots from a patient’s heart arteries during angioplasty, a procedure to open blocked arteries.

Although manually removing clots has become common medical practice, this study of more than 10,000 heart attack patients found no benefit in terms of reducing death, heart attack or heart failure in the six months after the procedure. Removing clots appears to have increased the risk of stroke in the month after clots were removed, the Canadian researchers report.

“There has been some controversy about removing blood clots during the treatment of heart attacks,” said lead researcher Dr. Sanjit Jolly, an associate professor of cardiology at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario.

A study in 2008 suggested that removing clots during an angioplasty might save lives, he said. “Guidelines changed based on this study,” Jolly noted. Another trial in 2013, however, suggested that removing clots was not beneficial, he added.

In this latest trial, researchers found that routinely removing clots was not beneficial, Jolly said.

Jolly isn’t sure why removing clots causes additional problems. It is possible that parts of the clot break off and travel elsewhere in the heart or brain, he said.

“This is an unexpected finding, and we want to confirm this in other studies,” Jolly said.

Jolly said there are mechanical methods of removing clots, which were not tested in this study. Whether these methods would have produced better results isn’t clear. “The jury is out on that. It needs to be tested in large trials,” he said.

However, preliminary results from small trials of mechanical clot removal have not been promising, Jolly noted.

Jolly said the lesson from his team’s trial is that clot removal should be used only as a rescue treatment when an angioplasty fails to clear an artery.

“As a routine therapy, clot removal is not beneficial and could have some significant downsides,” he said.

The results of the study were published online March 16 in the New England Journal of Medicine to coincide with a planned presentation of the findings at the American College of Cardiology’s annual meeting in San Diego.

For the study, Jolly and colleagues randomly assigned 10,732 patients undergoing an angioplasty after a heart attack to have clots manually removed or to not have them removed.

Among all the patients, 6.9 percent who had clots removed, and 7 percent of those who didn’t, died, had another heart attack or developed heart failure in the 180 days after the procedure.

In the 30 days after the procedure, 0.7 percent of the patients who had clots removed suffered a stroke, as did 0.3 percent of those who only had angioplasty, Jolly’s team found.

Dr. Gregg Fonarow, a professor of cardiology at the University of California, Los Angeles, said, “This is a very important and eagerly awaited clinical trial.”

A number of studies have suggested a benefit from manually removing clots during an angioplasty, but this trial found no clinical benefits for doing so, he said.

“These findings will likely have important implications for clinical practice,” Fonarow said.

More information

Visit the U.S. National Library of Medicine for more on angioplasty.

Source: HealthDay

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.