- Comparing Whey and Plant-Based Protein: Which is Best?

- How Long Does Nicotine Remain in Your System?

- The Best Time of Day to Drink Bone Broth to Maximize Health Benefits

- 8 Ways to Increase Dopamine Naturally

- 7 Best Breads for Maintaining Stable Blood Sugar

- Gelatin vs. Collagen: Which is Best for Skin, Nails, and Joints?

- The Long-Term Effects of Daily Turmeric Supplements on Liver Health

- Could Your Grocery Store Meat Be Causing Recurring UTIs?

- Are You Making This Expensive Thermostat Error This Winter?

- Recognizing the Signs of Hypothyroidism

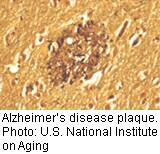

Mouse Study Suggests Immune Disorder May Play Role in Alzheimer’s

An immune system disorder may play a role in the development of Alzheimer’s disease, research in mice suggests.

Duke University researchers found that in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s, something goes wrong with certain immune cells that normally protect the brain, and the cells start to consume an important nutrient called arginine.

In mice, treatment with a drug called difluoromethylornithine (DFMO) blocked these immune cells from consuming arginine and prevented the brain plaques and memory loss associated with Alzheimer’s.

However, findings in animals are not always duplicated in humans.

The study was published April 15 in the Journal of Neuroscience.

“If indeed arginine consumption is so important to the disease process, maybe we could block it and reverse the disease,” senior study author Carol Colton, a professor of neurology and a member of the Duke Institute for Brain Sciences, said in a Duke news release.

DFMO is currently being tested in human clinical trials to treat some types of cancer, but has not been tested as a potential treatment for Alzheimer’s. In this study, DFMO was given to the mice before they developed Alzheimer’s symptoms. The researchers are now testing the use of the drug in mice after they develop Alzheimer’s symptoms.

Despite the findings, people should not eat more foods high in arginine or take dietary supplements in an attempt to protect themselves from Alzheimer’s disease, because it would do no good, Colton said.

“We see this study opening the doors to thinking about Alzheimer’s in a completely different way, to break the stalemate of ideas in AD,” she said. “The field has been driven by amyloid for the past 15, 20 years, and we have to look at other things because we still do not understand the mechanism of disease or how to develop effective therapeutics.”

More information

The U.S. National Institute on Aging has more about Alzheimer’s disease.

Source: HealthDay

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.