- Comparing Whey and Plant-Based Protein: Which is Best?

- How Long Does Nicotine Remain in Your System?

- The Best Time of Day to Drink Bone Broth to Maximize Health Benefits

- 8 Ways to Increase Dopamine Naturally

- 7 Best Breads for Maintaining Stable Blood Sugar

- Gelatin vs. Collagen: Which is Best for Skin, Nails, and Joints?

- The Long-Term Effects of Daily Turmeric Supplements on Liver Health

- Could Your Grocery Store Meat Be Causing Recurring UTIs?

- Are You Making This Expensive Thermostat Error This Winter?

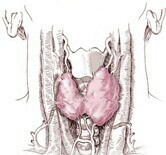

- Recognizing the Signs of Hypothyroidism

Even Slightly Overactive Thyroid Linked to Higher Fracture Risk

Even people who only have a mildly overactive thyroid gland face an elevated risk for fractures in the hips or spinal area, a new review suggests.

“Subclinical hyperthyroidism” is a condition in which an overactive thyroid gland produces too much of the hormones that control basic metabolism but there is a lack of symptoms, and hormone readings are normal in blood tests.

Past research has shown that more pronounced cases of hyperthyroidism are associated with a raised fracture risk, the reviewers explained. But it hasn’t been entirely clear whether the same holds true for milder forms of the condition.

The Swiss reviewers looked at 13 past studies involving more than 70,000 patients to try to answer that question.

“There have been several studies that have previously suggested an increased risk for fractures, but up until now it wasn’t clear if it was a real association,” explained study author Dr. Nicolas Rodondi, head of the ambulatory care department at Bern University Hospital. “But, based on our work, we can say that it is clear that these patients do have an increased risk for fracture.”

But why?

“That is not exactly clear,” Rodondi said. “But we know that thyroid hormones have a direct impact on bone metabolism, and increased thyroid function would increase the metabolic impact on bones. So, one explanation is accelerated bone turnover, meaning an increase in bone destruction and re-modeling.”

Rodondi and his colleagues published their findings in the May 26 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Among the pool of patients studied, a little more than 3 percent had subclinical hyperthyroidism. Nearly 6 percent had the opposite problem, a condition known as hypothyroidism.

Ultimately, the review team found no link between having an underactive thyroid (hypothyroidism) and increased fracture risk.

But those with a symptomless but overactive thyroid did appear to face a higher risk for bone breakage in the hip and spinal regions. The finding held up regardless of age or gender, though the research team said it did not have enough data to comment on how race might figure into the equation.

While the study found an association between mild hyperthyroidism and fracture risk, it did not prove that the condition causes fractures.

The study team did not call for any changes to current treatment guidelines for hyperthyroidism. One reason is that it remains unclear whether treating subclinical hyperthyroidism will actually help to reduce fracture risk.

“Of course, we always treat the condition when it’s diagnosed,” said Rodondi. “But there are a lot of other risk factors that impact fracture risk, particularly among the elderly, including low physical activity, low calcium levels and low vitamin D levels. So, we don’t know if treating hyperthyroidism alone will have an impact,” he explained.

“It also remains controversial whether all elderly people should be routinely screened for hyperthyroidism, which is something we cannot address based on this study,” Rodondi added. “And the problem, of course, is that most of the patients with a subclinical condition have no symptoms. So if we don’t screen, we don’t know there’s a problem.”

Dr. James Hennessey, director of clinical endocrinology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, was not involved with the review but was familiar with the findings. Clinicians “are caught in a dilemma,” he said.

“We don’t generally screen for subclinical hyperthyroidism because we agree more research is needed. But frankly, those controlled, randomized studies [the “gold standard” for research] are not likely to be done anytime soon. So, we wait for obvious symptoms to appear, even as we become, at the same time, more aggressive in thinking about thyroid disease’s impact on bone density and fracture risk,” Hennessey explained.

“But what this study does is further substantiate that there is a fracture risk with persistent hyperthyroidism,” he added. “We’ve known that for a while. But this gives us some more evidence. And it underscores that the issue really should be taken seriously.”

More information

There’s more on hyperthyroidism from the Endocrine Society.

Source: HealthDay

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.