- Double Mastectomy May Offer No Survival Benefit to Women With Breast Cancer

- Toxic Lead Found in Cinnamon Product, FDA Says

- Certain Abbott Blood Sugar Monitors May Give Incorrect Readings

- Athletes Can Expect High Ozone, Pollen Counts for Paris Olympics

- Fake Oxycontin Pills Widespread and Potentially Deadly: Report

- Shingles Vaccine Could Lower Dementia Risk

- Your Odds for Accidental Gun Death Rise Greatly in Certain States

- Kids From Poorer Families Less Likely to Survive Cancer

- Tough Workouts Won’t Trigger Cardiac Arrest in Folks With Long QT Syndrome

- At-Home Colon Cancer Test Can Save Lives

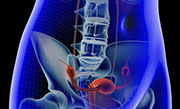

New Hope for Early Detection of Ovarian Cancer

MONDAY, Aug. 26A simple blood test combined with an ultrasound exam may help doctors catch ovarian cancer while it’s still treatable, a new study shows.

Ovarian cancer is a silent killer. It strikes with few, if any, symptoms. By the time a woman knows she has it, the cancer is often advanced and the outlook grim.

This new study “is a ray of excitement,” said researcher Dr. Karen Lu, a professor of gynecologic oncology at the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. “The important message is that this shouldn’t change clinical practice right now. We don’t have enough data.”

Unlike breast, cervical or colon cancer, there’s no reliable screening test to detect the disease. Many approaches to ovarian cancer screening have been tried, but none has proven accurate enough to use in the general population. Most produce high numbers of false positive results, which require doctors to perform invasive surgeries to rule out cancer.

Because ovarian cancer is rare — about 1 in 2,500 postmenopausal women in the United States will receive an ovarian cancer diagnosis in their lifetime — any screening test that produces many false positives would harm far more women than it would help, making doctors very cautious about the tests they try.

In the new study, which ran for 11 years and included more than 4,000 women, most of whom were white, a two-stage screening method appeared nearly 100 percent accurate at ruling out these harmful false alarms in postmenopausal women.

A much larger study — of more than 200,000 women — testing the two screening methods is under way in the United Kingdom. Preliminary results from that trial, released in 2009, were positive, and researchers are eagerly awaiting the final results, which are due in 2015.

“We really need to wait for the U.K. data before we’re able to institute this as a screening method,” Lu said.

The new screening method combines two existing tools: a blood test that measures a protein shed by tumor cells called CA-125 and an ultrasound exam to give doctors a look at the ovaries.

Those two tests have been used together before, with disappointing results. But the current research differs in that it takes into account fluctuations in a woman’s blood test results. The important thing isn’t any single measure of CA-125 in the blood, but how it changes over time, the researchers said.

For the new study, published online Aug. 26 in the journal Cancer, the researchers recruited post-menopausal women between the ages of 50 and 74 who had no personal or family history of ovarian cancer. Women were screened, on average, for about four years.

Each year, women in the study were given a CA-125 blood test. Researchers fed the women’s age and test results into a mathematical formula called Risk of Ovarian Cancer Algorithm, or ROCA, which was developed using a database of CA-125 test results from thousands of women in the United States and Sweden.

If the results came back as low risk, women were asked to repeat the test the following year. Women with intermediate-risk results were told to have another blood test in three months, while those with high-risk results were referred for a transvaginal ultrasound exam, a pain-free test that lets doctors see the size and shape of the ovaries.

If the ultrasound results also were abnormal, women were referred to surgery.

Over 11 years, 83 percent of women remained at low risk and had to return only for an annual blood test. About 14 had at least one intermediate-risk result that caused them to return in three months for a follow-up test. Roughly 3 percent were deemed high risk and were referred for an additional ultrasound exam.

Ten of the 117 women referred for ultrasound exams had suspicious results and underwent subsequent surgeries. Of those, seven had some type of cancer, while three had benign tumors. Four of the patients had early stage cancers. All of the women are still alive and free of disease following treatment for their cancers.

One expert said these results, along with the early results achieved in the British trial, are very promising.

“I was more excited reading this study than I have been in a really long time,” said Debbie Saslow, director of breast and gynecologic cancers for the American Cancer Society in Atlanta.

“Not only was [the screening] finding cancers in both of those studies, but it was finding them early,” Saslow said. “That’s what we want to do.”

Saslow pointed out that the study was small, however, and it had no control arm to help researchers see what would have happened to a similar group of women who were not screened over the same time period.

Whether the findings would apply to younger women or blacks and Hispanics also is unknown.

More information

For more information on ovarian cancer, head to the U.S. National Cancer Institute.

Source: HealthDay

Copyright © 2024 HealthDay. All rights reserved.