- Double Mastectomy May Offer No Survival Benefit to Women With Breast Cancer

- Toxic Lead Found in Cinnamon Product, FDA Says

- Certain Abbott Blood Sugar Monitors May Give Incorrect Readings

- Athletes Can Expect High Ozone, Pollen Counts for Paris Olympics

- Fake Oxycontin Pills Widespread and Potentially Deadly: Report

- Shingles Vaccine Could Lower Dementia Risk

- Your Odds for Accidental Gun Death Rise Greatly in Certain States

- Kids From Poorer Families Less Likely to Survive Cancer

- Tough Workouts Won’t Trigger Cardiac Arrest in Folks With Long QT Syndrome

- At-Home Colon Cancer Test Can Save Lives

A Better Test for Down Syndrome?

A new test that examines fetal DNA from a mother’s blood is more accurate at spotting chromosomal abnormalities such as Down syndrome than standard tests offered to pregnant women, a new study indicates.

Scientists found that the blood test, known as cell-free DNA, performed up to 10 times better than other noninvasive tests currently used to screen for “aneuploidy” — one or more missing chromosomes that can signal conditions such as Down or Edwards syndromes. Both can cause intellectual and physical disabilities. Infants born with Edwards syndrome rarely live beyond one year.

“We had suspected the DNA test would perform well, but what was needed was this head-to-head comparison with the current standard of care,” said study author Dr. Diana Bianchi, executive director of the Mother Infant Research Institute at Tufts Medical Center in Boston. “The cell-free DNA has a much lower false positive rate, which means fewer women will be alarmed unnecessarily and fewer will have to go to a genetic counselor or have an invasive procedure” to determine if their baby has a chromosomal defect.

The study, funded by Illumine Inc., the San Diego manufacturer of the new test, is published Feb. 27 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Noninvasive prenatal screening began in the 1970s. Current tests looking for abnormalities include ultrasound imaging and maternal blood tests measuring a protein that’s considered an indicator for Down syndrome.

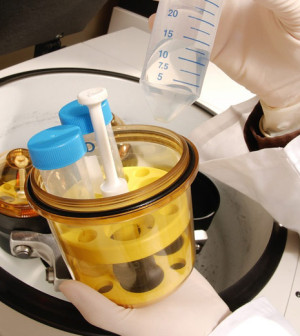

If these screening tests predict an increased risk for chromosomal defects, pregnant women are typically urged to undergo invasive testing such as amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling, which extract fetal DNA from the amniotic fluid or placenta, respectively. While these procedures can tell for certain if a fetus is abnormal, they also raise the risk of miscarriage.

At 21 centers in the United States, Bianchi’s team collected blood samples from more than 1,900 pregnant women, average age 30, undergoing standard aneuploidy screening. The researchers compared the results with those obtained from cell-free DNA tests.

While the new technique, available since 2011, had been tested previously among women at high risk of bearing children with chromosomal abnormalities, this trial was the first among a general population of pregnant women with typical risks.

The study found that incorrect or “false positive” results for chromosomal defects stemming from cell-free DNA testing were significantly lower than those with standard screening — 0.5 percent compared to 4.2 percent for Down and Edwards syndromes combined.

“I think this is a stronger test,” said Dr. Edward McCabe, senior vice president and chief medical officer of the March of Dimes, who was not involved in the study. “I think more research is needed … but I’m comfortable with the conclusion here that if your [cell-free DNA] test is negative, that’s a strong indication your baby’s not affected” by aneuploidy.

Bianchi agreed that additional research is needed before the cell-free DNA test can replace standard screening tests among low-risk pregnant women. She also noted that the cost of the new test is a concern — from $500 to $2,000 depending on different factors, although insurance companies typically cover it for high-risk women. Obstetricians would also need to be educated about its use, she said.

More information

The National Down Syndrome Society offers more information about the chromosomal condition.

Source: HealthDay

Copyright © 2024 HealthDay. All rights reserved.