- The Best Time of Day to Drink Bone Broth to Maximize Health Benefits

- 8 Ways to Increase Dopamine Naturally

- 7 Best Breads for Maintaining Stable Blood Sugar

- Gelatin vs. Collagen: Which is Best for Skin, Nails, and Joints?

- The Long-Term Effects of Daily Turmeric Supplements on Liver Health

- Could Your Grocery Store Meat Be Causing Recurring UTIs?

- Are You Making This Expensive Thermostat Error This Winter?

- Recognizing the Signs of Hypothyroidism

- 10 Strategies to Overcome Insomnia

- Could Artificial Sweeteners Be Aging the Brain Faster?

A Promising New Therapy Against OCD?

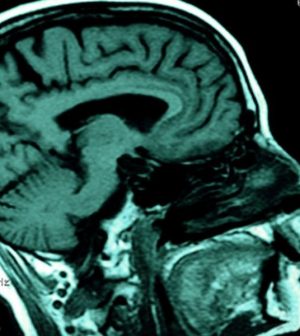

Noninvasive electrical stimulation of the brain, fine-tuned to specific “circuitry” gone awry, might help ease obsessive-compulsive behaviors, an early study hints.

Researchers found that the brain stimulation, delivered over five days, reduced obsessive-compulsive tendencies for three months, though in people who did not have full-blown obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

It’s too early to say whether the approach can be translated into an OCD therapy, said researcher Shrey Grover, a PhD student in psychological and brain sciences at Boston University. “We need more research to replicate these findings. It will take time before this is widely available.”

But the work, described online Jan. 18 in Nature Medicine, builds on a body of research into the underpinnings of OCD.

Research has shown that people with OCD have difficulty processing “rewards” from the environment, Grover explained. So they become reliant on certain rituals, whether it’s compulsively washing their hands, making sure household items are placed a particular way or checking that appliances are turned off.

Scientists have also found that certain brain activity patterns are associated with those symptoms.

In fact, abnormalities in the brain’s circuitry are involved in a number of psychiatric conditions, according to Dr. Alon Mogilner, director of the Center for Neuromodulation at NYU Langone Health, in New York City.

“Neuromodulation” is a broad term for therapies that use electrical pulses to alter the firing patterns of nerves.

Mogilner, who was not involved in the new study, sometimes treats OCD using deep brain stimulation (DBS), which involves surgical implantation of electrodes into the brain, with the goal of interfering with abnormal electrical activity in specific brain areas.

DBS is reserved for the toughest cases of OCD, Mogilner said, where people have debilitating symptoms that fail to respond to standard behavioral therapy and medication (usually SSRI antidepressants).

“It’s for the situations where people can’t leave the house because they have to keep washing their hands,” Mogilner said.

DBS helps about 50% to 60% of the time, according to Mogilner. But that leaves a significant portion who do not improve.

And for some people with OCD, the idea of having electrodes implanted in the brain is one more thing to obsess over, Mogilner noted.

Noninvasive brain stimulation would avoid the risks of surgery, he said, and possibly give some patients an option they could live with.

One noninvasive approach — transcranial magnetic stimulation — was recently approved in the United States for OCD. It’s typically done in daily sessions, five days a week, for about six weeks, according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness.

For the new study, the Boston researchers recruited 124 volunteers. None had OCD, but many scored high on the obsessive-compulsive scale. Those behaviors, Grover explained, exist on a spectrum: It’s not that people either have OCD or no symptoms at all.

The researchers used a newer neuromodulation technique called transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS), where electrodes on the scalp deliver an oscillating current at a chosen frequency that interacts with the brain’s natural activity.

First, the researchers found they were able to influence volunteers’ “reward-based” behavior during a standard test, by using tACS currents that were individualized to each person’s natural frequency in the brain’s reward-processing network.

Then, in a separate experiment, the investigators found that applying the brain stimulation for 30 minutes on five consecutive days reduced participants’ obsessive-compulsive behaviors for up to three months.

There are plenty of questions ahead, including whether those effects can be replicated in OCD patients, Grover said.

Mogilner said the “personalized” aspect of the tACS approach is interesting: He likened it to tuning in to not only the brain circuits involved in the behavior, but the “sounds” in those circuits. Still, he said, the degree to which that improves the effectiveness for any one person remains to be seen.

Another big question, Mogilner said, is what happens in the long run: How long could any benefits from tACS last, and how often would sessions need to be repeated?

Grover agreed. “We want strong effects that are sustainable,” he said. “We don’t know if this will be as effective as DBS.”

On the big-picture side, the precise causes of OCD remain unknown. The current findings, Grover said, do not prove that abnormal brain activity patterns are the “origin” of OCD: They might reflect some other root cause.

More information

The National Alliance on Mental Illness has more on obsessive-compulsive disorder.

SOURCES: Shrey Grover, PhD student, psychological and brain sciences, Boston University, Boston; Alon Mogilner, MD, PhD, neurosurgeon and director, Center for Neuromodulation, NYU Langone Health, New York City; Nature Medicine, Jan. 18, 2021, online

Source: HealthDay

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.