- Double Mastectomy May Offer No Survival Benefit to Women With Breast Cancer

- Toxic Lead Found in Cinnamon Product, FDA Says

- Certain Abbott Blood Sugar Monitors May Give Incorrect Readings

- Athletes Can Expect High Ozone, Pollen Counts for Paris Olympics

- Fake Oxycontin Pills Widespread and Potentially Deadly: Report

- Shingles Vaccine Could Lower Dementia Risk

- Your Odds for Accidental Gun Death Rise Greatly in Certain States

- Kids From Poorer Families Less Likely to Survive Cancer

- Tough Workouts Won’t Trigger Cardiac Arrest in Folks With Long QT Syndrome

- At-Home Colon Cancer Test Can Save Lives

Clearing More Arteries Works in Angioplasty Trial

SUNDAY, Sept. 1Heart attack patients who undergo angioplasty for a clogged artery that caused the attack may do better if other clogged arteries are done at the same time, new research suggests.

Patients who had multiple coronary arteries opened with angioplasty techniques during emergency surgery were 65 percent less likely to die, have a repeat heart attack or chest pains known as angina during the follow-up period than those who only had the so-called “culprit artery” opened.

The randomized trial of 465 patients in Britain was halted early, in January 2013, when the results in the group in which multiple arteries were opened became evident, the researchers reported.

The study is published online Sept. 1 in the New England Journal of Medicine to coincide with presentation of the results at the European Society of Cardiology 2013 Congress in Amsterdam.

While the idea has been discussed before, “until the results of this trial were known, there was uncertainty” about whether to take the preventive approach of opening more arteries, said study researcher Dr. David Wald of the Queen Mary University of London.

“It’s a very aggressive approach,” said Dr. Ravi Dave, a cardiologist at the University of California Los Angeles Medical Center, Santa Monica, who reviewed the findings but was not involved in the study. “It’s counterintuitive to the way cardiology is [traditionally] practiced,” he added, because doctors typically monitor the other arteries after angioplasty on one.

However, Dave noted, the researchers showed in the trial that other coronary arteries may be equally unhealthy as the artery causing the heart attack.

For the study, which ran from 2008 through 2013, Wald and his colleagues evaluated 465 patients who had a type of heart attack known as STEMI (acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction). They studied this type because the artery causing the heart attack is easily identified. They assigned about half of the 465 patients to the preventive angioplasty group, in which the extra vessels were opened, and the other half to the regular angioplasty group.

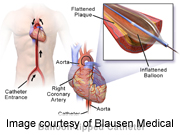

After the artery in which the heart attack occurred was opened, the preventive group also had angioplasty on other arteries that were more than 50 percent blocked. In angioplasty, a balloon is inserted into the artery, then expanded to restore blood flow. After that, a scaffolding-like device known as a stent is inserted to keep the artery open.

When Wald’s team compared the preventive group to the traditional group, they found that death rates from heart causes after the angioplasty were nine per 100 patients, compared with 23 per 100 patients in the traditional group.

Complications, such as strokes related to the procedure, or excessive bleeding, were similar in both groups.

“I think this study is pivotal,” said Dr. Ted Bass, president of the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions and chief of cardiology at University of Florida Health-Jacksonville. He reviewed the study findings.

In the United States, Bass added, multiple vessels may be opened up during elective angioplasty, but when emergency angioplasty is done on someone having a heart attack, standard practice is to only open the artery involved, with some exceptions.

“The rationale behind that is, the patient is already quite sick, and any time we go to another blood vessel and try to fix a blockage, there is a small likelihood things could go wrong,” Bass said. “It’s a little bit of a minefield.” Blood vessels are more reactive after a heart attack, he said.

Under guidelines issued by his society and other organizations, he said, the thinking has been that, for most patients “you should not do more than just fix the artery involved in the heart attack, but the level of evidence [for this approach] has been somewhat weak.”

The new approach, Bass said, wouldn’t be implemented in the United States until more research confirms the results and organizations have a chance to review the evidence.

UCLA’s Dave can see pros and cons of the approach that was studied.

“This is a very convenient thing for the patient to have everything done on one occasion,” he said. “But it could be overtreatment.”

Wald, the lead study author, noted that “the initial cost of preventive [angioplasty] is higher, but there would be a reduced cost thereafter because of a reduced need for hospital admission, cardiac investigations and repeat procedures.”

Wald reported he was a director of Polypill Ltd, a medication program for prevention of heart attack and stroke.

More information

To learn more about angioplasty, visit the U.S. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Source: HealthDay

Copyright © 2024 HealthDay. All rights reserved.